With “42,” the true story of Brooklyn Dodger great Jackie Robinson, due out on Friday, Off The Bench is going to run a story we did for Vassar’s MODFEST in the beginning of February. The event was opened by keynote speaker Sidney Plotkin providing a beautiful lesson on the House Un-American Activities Committee, headed by Senator Joseph McCarthy, and its function against the tenants of both the Constitution of the United States and the founding ideals of the country. The House Un-American Activities Committee levied charges against many members of Hollywood and other rumored Communists. At the time, accusations of Communism were just as damning as admissions, and many of the people who testified before the committee found themselves blacklisted and unable to work.

Max and I were asked to speak on Jackie Robinson’s involvement in the situation. While we didn’t know much about the story when we were first approached, what we soon uncovered was fascinating and provided some insight into all that Robinson dealt with and the immense repercussions that followed his every move. For two kids born in the 90’s, the pressure and backlash is unimaginable, but such was the life of Jackie Robinson.

What follows is transcript of the speech that Max and I gave on February 4 of this year.

Jackie Robinsons’s is a name that many of us have heard before and know well. Even those hard pressed to call themselves sports fans know that Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier, becoming the first African American to enter the lucrative realm of professional sports in this country. Those of us a little bit more in tune with the story may know that Robinson will be the subject of a major motion picture, featuring Harrison Ford, to be released this summer.

Jackie Robinson’s long road to the Major Leagues took him through UCLA, where he became the school’s most decorated athlete ever, the US Army at the height of World War II, and the all black Negro Leagues, before he signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers that paid him $600 per month.

On April 15, 1947, Robinson made his Major League debut in front of more than 26,000 fans at the storied Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. More than 14,000 of those in attendance that day were black.

Robinson took the major leagues by storm, both on and off the field. Living up to the challenge to “have guts enough not to fight back,” Robinson tried his best to put the off field distractions aside. Though he encountered intense racism during his first years with Dodgers, Robinson excelled on the diamond, winning the 1947 Rookie of the Year award. Three years into his career, in 1949, he was honored as the National League’s Most Valuable Player when he led the league in both batting average and stolen bases. Eventually, in 1962, Robinson was elected to join legendary players such as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Cy Young in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

One of the men instrumental to positioning Robinson to play in the Major Leagues was noted actor, singer, and civil rights activist Paul Robeson. In the early 1940’s Robeson had spoken to the owners and commissioner of Majo League Baseball and made large strides in convincing him to one day allow the integration of the sport.

Robeson had become enamored with the lack of racial bias he encountered on his trips to the Soviet Union and, in April 1949, he told the Paris Peace Conference in Paris, France that American blacks would not support a war between the US and the USSR.

The exact quote from Mr. Robeson is hard to discern but the message that Robeson delivered drew the interest of the House Un-American Activities Committee and he was brought before Congress to disavow his Communist ideals.

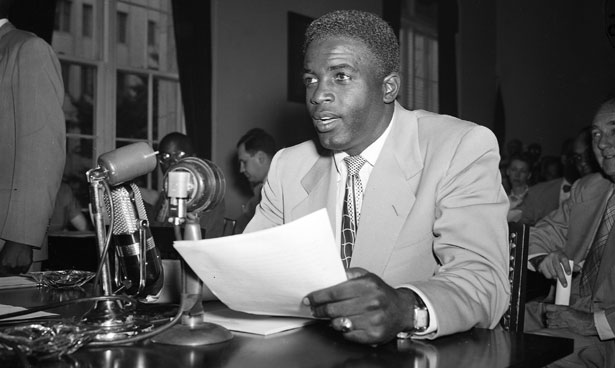

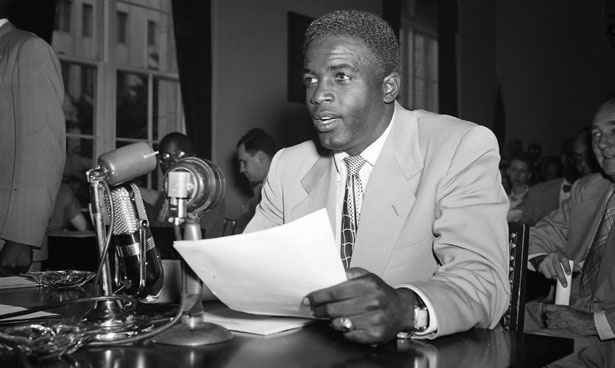

As part of the hearing, Jackie Robinson was called to testify, in part to renounce Robeson and in part to discuss the potential communist leanings of the black population of the United States. Robinson, as you will see in the video, was a bit hesitant to testify.

Jackie was unsure of his role as a public figure at the time and considered himself more of a baseball player than political activist. In his autobiography, published in 1972, Robinson explained his reasoning for testifying: “the newspaper accounts seemed to picture the great singer as speaking for the whole race of black people. I wasn’t about to knock him for being a Communist or a Communist sympathizer. That was his right. But I was afraid Robeson’s statement might discredit blacks in the eyes of whites.”

Robinson’s testimony was well planned, well thought out, and crafted with the support of his bosses with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He made a point of not defending the loyalty of African Americans, saying that any loyalty that needed defense “can’t amount to much in the long run.”

He said that like all groups, black Americans were diverse–made up of communists, pacifists, and fierce patriots. He condemned the idea of calling any minority or group radical, saying that such a concept “gets people scared because one Negro, addressing a communist group in Paris, threatens an organized boycott by 15 million members of his race.”

On balance, the reaction to Robinson’s testimony was positive. Though some in the black community thought he bowed to the white establishment, most observers thought that the All-Star second basemen was successful in adeptly diffusing the perception that all blacks were communists.

Robinson remained a prominent figure in the civil rights movement for the rest of his life and even after his death in 1972. He continued to be praised thanks to his role in integrating the national pastime and as an ambassador for the black community. In 2008, The New York Times’s Dave Anderson wrote that “More than a decade before Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King put the phrase civil rights into the nation’s vocabulary, Jackie Robinson taught millions of baseball’s white fans that black was beautiful.”

-Sean Morash and Max Frankel