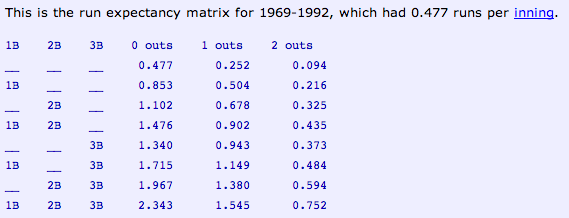

We have all heard the argument that the sacrifice bunt is maybe not such a good idea, but I never really knew why the nerds of baseball have taken such a strong stand against it. It turns out that the sacrifice bunt can be a weapon in certain run-scoring situations, but across a large sample (1969-1992) in Major League games, outs are a precious commodity. I will present a table from “The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball” and then discuss some caveats and important footnotes. And before you ask, yes, I’m asking for The Book for Christmas this year.

First question: how applicable is the run scoring environment of 1969-1992 to today’s game? In 2013, we had .464 runs per inning, which by my estimation makes these small differences in run expectancy all the more important. Or, as we’ll discuss later, playing for one run in a worse scoring environment may be a better managerial move.

Let’s look at what this table tells us about the sacrifice bunt by looking at each scenario where a sacrifice bunt is typically used (Run expectancy in parenthesis)

- Runner on 1B, 0 outs (.853). A Successful bunt means Runner at 2B, 1 out (.678). Difference= -.175

- Runner at 1B, 1 out (.504). A successful bunt means runner at 2B, 2 out (.325). Difference= -.179

- Runner on 2B, 0 outs (1.102). A Successful bunt means Runner at 3B, 1 out (.943). Difference= -.159

- Runner at 2B, 1 out (.678). A successful bunt means runner at 3B, 2 out (.373). Difference = -.305

- Runners at 1B, 2B, 0 out (1.476). Successful bunt runners at 2B, 3B, 1 out (1.380). Difference= -.096

- Runner at 1B, 2B, 1 out (.902). Successful bunt means runners at 2B, 3B, 2 out (.594). Difference= -.308

A cursory look at the above gives us a pretty good idea why the nerds are up in arms. We do however, learn that the bunt with runners on first and second with nobody out seems to be the least bad idea. I always liked that bunt and am happy that my baseball upbringing is supported by these facts.

Playing simply by the numbers means that we ignore situations of overmatched pitchers at the plate hitters. Now, in a situation where the hitter is overmatched and the manager is forced to take the lesser of two evils, of course it is better to advance the runner at the expense of an out. I’m thinking of extreme examples here where the likelihood that a hitter strikes out is very high while likely undervaluing the difficulty of performing a successful bunt.

Finally, we need to address the caveats of the above matrix. Primarily, it is calculated in the Major Leagues and we are assuming that the bunt is always fielded well defensively. Across different talent levels, different valuations of defensive ability likely adjust the outcomes–and thus, the relative situational values.

I’m not as calcified as some of the baseball nerds on the rigidity of large samples. I’ve played the game and know that every contest is slightly different, with any number of variables at play (including eye color if you ask Josh Hamilton). Given the above matrices and above bullet points, maybe its a good idea to start giving some good hitting pitchers more credit. They give their teams a better chance to score runs and those are what you needs to win games. If only your two favorite baseball bloggers wrote on that this week…

Baseball is played across many age groups, and at many different skill levels. At all levels, the object is to score runs. It is unclear how far reaching is the useful application of the above information–should Division III head coaches spurn the sac bunt with the same frigidity seemingly appropriate for Big League skippers?–but it does seem clear that at the Major League level, the sacrifice bunt is usually a bad idea.

-Sean Morash

Stat of the Day: The Red Sox issued the fewest IBB in baseball this year with 10; the Cardinals the second fewest in the NL with 26. (Do I smell a post on the efficacy of the IBB…?)