Most baseball people are aware that Major League Baseball has seen a massive decline in runs scored over the last few years. So much so that while 2013 was dubbed the “year of the pitcher,” 2014 then saw even fewer runs scored (“year of the better pitcher?”). Teams scored an average of 4.07 runs per game in 2014, the lowest figure since 1981. Among the over-exposed talking heads and color commentators, theories center on rising pitch velocities, improved bullpen management, increased use of the defensive overshift, and the true dawn of the post-PED era. While these theories have merit, they are certainly not the only ones worthy of discussion.

It seems most theories fail to account for the occasional position player or manager who, with whatever help from Dorothy in Oz, has found a brain, and become capable of making adjustments. As pitchers and pitching evolve, so too do hitters and hitting. The guys with the bats figure out new ways to beat their opponents; they make adjustments and adapt.

The game’s changed over the years–not just in uniforms or facial hair–but in style of play. Offensive theories seem to ebb and flow from a strikeout/home-run focus to emphasizing contact and speed. Historically, MLB has not left it up to the hitters to make all of the adjustments. MLB rule changes in reaction to new heights of pitcher success, including the all-time high in strikeouts, are not without precedent. In 1968, the mound was lowered after an ERA of 2.98 was the norm across the league. Baseball hasn’t reached such dire times just yet, but it is becoming increasingly obvious that the offensive depression is a norm not an anomaly, and further that we have arrived here via a series of small rule changes benefiting the pitcher.

In no way is this an attempt to summarize every rule change that may or may not have lead to this reduced run scoring environment, but to instead highlight a few important trends that are not getting enough attention.

The first, and most obvious is the institution of drug testing in baseball. But, stopping the nonsense of players running around looking like this, or making transformations like this, was necessary, and not solely responsible for the current doldrums of 4.07 runs per game. There are other, more nuanced shifts afoot.

The Strike Zone

Jon Roegele at The Hardball Times came out with a great piece yesterday titled “The Strike Zone Expansion is Out of Control.” Roegele’s analysis, using pitch f/x data from all 30 teams since 2008 finds that the strike zone is 39 square inches larger today than it was in 2008.

| AVERAGE SIZE OF CALLED STRIKE ZONE (SQ. IN.) |

|---|

| Year | Size |

| 2008 | 436 |

| 2009 | 435 |

| 2010 | 436 |

| 2011 | 448 |

| 2012 | 456 |

| 2013 | 459 |

| 2014 | 475 |

It’s not just that the strike zone is expanding, it’s how the strike zone is expanding. Roegele found that the strike zone has significantly shifted downward, while pinching in at the sides.

| AVERAGE SIZE OF CALLED STRIKE ZONE BELOW 21″ (SQ. IN.) |

|---|

| Year | Size |

| 2008 | 0 |

| 2009 | 0 |

| 2010 | 6 |

| 2011 | 11 |

| 2012 | 19 |

| 2013 | 30 |

| 2014 | 47 |

These numbers signal an important shift in the game of baseball. As technology improves, umpires are scrutinized at every turn. For the most part they do a fantastic job, especially as pitches move faster and more unpredictably than ever before. But as umpires are constantly being reviewed based on a digital rendering of the strikezone, their execution of that strikezone has become “imperfectly perfect.” (We can all relate to the feeling of watching a catcher pick a slider in the dirt, only to see the PitchTrax register it at the knees.) This is not a fault of the umpires themselves, but of a macro shift toward embracing technology.

The adjustments that I discussed earlier from hitters and pitchers are not restricted to reactions to one another. Hitters and pitchers react to external inputs as well. For example, in response to the lower strike zone, pitchers started throwing more pitches (about 1.5% more since 2008) low, between 18″ and 24″. In turn, hitters swung at about 4% more pitches in that same area in 2014 than they did in 2008.

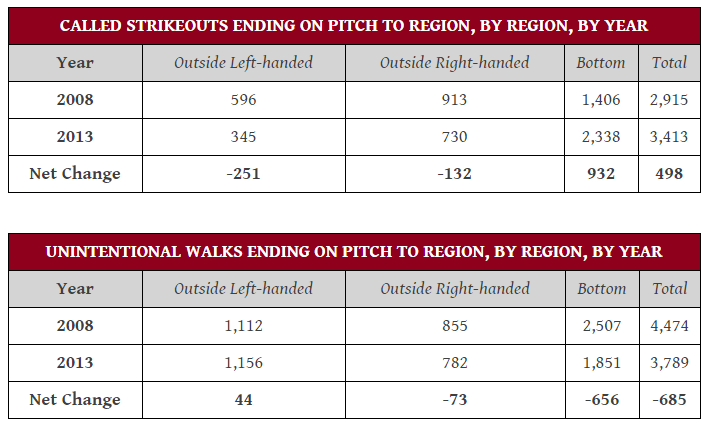

The main crux of Mr. Roegele’s argument is that this change in strike zone has directly lead to fewer runs being scored. Consider:

The effect that this downward expansion of the strike zone has had on walks and strikeouts outweighs the effect of the narrowing. Additionally, the trend outlined in the figures above is likely much worse for hitters than merely the pitches that end the at bat. Any baseball player is painfully aware of the effect that a single pitch can have on the outcome of an at bat. (Ask Matt Kemp.) Even the great Mike Trout was just a .269/.336/.541 hitter after a first pitch strike.

The good news for the MLB is that it will not require sweeping institutional change to return to the days of higher scoring. The strikezone, as defined in the rule book is:

That area over home plate, the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level a line at the hollow beneath the knee cap. The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.

I’m 5’10 (on a good day) and the area from my office floor to the bottom of my knee cap measures approximately 19 inches (or 4.2 iPhone 4S’s). With that knowledge, it seems like umpires are simply more accurately calling the low strike since 2008. Likely, a return to the 1988-1996 definition of the strike zone, from the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants to the lower level at the top of the knees, would prove beneficial to hitters.

The Skinny Bat

Where modern fashion has transitioned the every man to a skinnier jean, MLB has transitioned its players to a skinnier bat. Nick Scott at Royals Authority did a great job of outlining this rule change and the effect that it could be having upon the game.

Essentially, before the 2010 season, MLB made an adjustment to rule 1.10 (a) stating that

The bat shall be a smooth, round stick not more than 2.61 inches in diameter at the thickest part and not more than 42 inches in length. The bat shall be one piece of solid wood.

Prior to this, the rule read exactly the same, but allowed bats 2.75 inches in diameter.

Rob Neyer shot this one down recently, as his contact (Major League Baseball’s Senior Vice President and General Counsel, Labor Relations) asserted that no players in 2009 were using a bat larger than 2.61″. However, that statement conflicts with Nick Scott’s initial findings that something like 35% used 2.75″ bats.

Whatever the true figure, making an adjustment to a rule that hadn’t been changed since 1895 likely had some effect. (In 1895, MLB increased the size allowable from 2.5” to 2.75”, so the 2010 ruling decreased the allowable barrel size for the first time in 115 years.)

The Dense Bat

In 2008, almost one bat per game was shattered, creating safety concerns for both players and fans. MLB reports that that that number has been cut in half thanks to adjustments in the quality of wood and regulations on the minimum size of the handle (now 86/100 inch).

Where MLB is selling this as an attempt to make the game safer (a noble and just cause), it has also lead to a decrease in the number of players using their preferred style of bat. In 2008, some 60% of MLB players used maple bats. That number has risen to nearly 70%, but not without regulation. Bat manufacturers are no longer allowed to make bats that are less than 0.0240 pounds per cubic inch. No real word on if this has had a dramatic effect on the game, but making bats denser (heavier) surely changes things–especially when the PEDs that allowed them to swing harder and faster have been phased out.

Under the banner of safety and accuracy, the MLB has perpetrated a multi-platform campaign over the past decade or so. Players and umpires alike are more closely monitored; bats have become smaller and strikezones bigger; advancements in scouting and information technology allow managers to exploit hitters’ every weakness. Many would argue that these changes are insufficient to produce such significant effects on offensive output, but I disagree. Hitters are notoriously fragile of psyche, and after all: baseball is 90 percent mental and only half physical.

-Sean Morash