Rivalries add a necessary spice to the long baseball season. They add the human element and real emotions not found in mere statistics and standings. Perhaps the greatest personal rivalry in baseball history was that between the New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson and Boston Red Sox backstop Carlton Fisk. There have been plenty of other great personal rivalries, but few lasted as long or were more prominent. It involved two great players, both leaders of their teams, playing the same position, closely matched by geography, playing for traditional team-rivals that battled each year for the league lead. This was no made-for-television/media-driven thing; it was real and it was spectacular. The Munson-Fisk rivalry came to dominate and define the decade of the seventies in the American League.

It was a private war fought in front of millions. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the competition and aversion between the two started. There’s an old story that it began in September of 1971. Fisk, then an eager late-season call-up who was in the habit of racing batters down the first baseline to back up the play, nearly beat Munson, who prided himself on his speed, to the bag on a close play, thereby embarrassing the prideful Munson. Although no confirmatory evidence of such a play can be found in box scores, the story is too exquisite to discount, given what came later. But while the incident, if something did indeed occur, would have been irritating to Munson, he lived to be irritated, he thrived on it; he looked for little things to get mad at opponents about. Had Fisk just been an anonymous young player who faded the next year, it would have been quickly forgotten.

Sometime during the 1972 season–when Fisk began to take the national spotlight and All-Star votes–is when he really first inspired Munson’s disdain. Munson had been the overwhelming choice as the best catcher in the league until Fisk showed up. He had been the only catcher in league history to be selected Rookie of the Year—until Fisk showed up (and Fisk trumped him by being the first player to be selected unanimously). It drove Munson to distraction that fans and writers could even suggest that this interloper could possibly be better than he was.

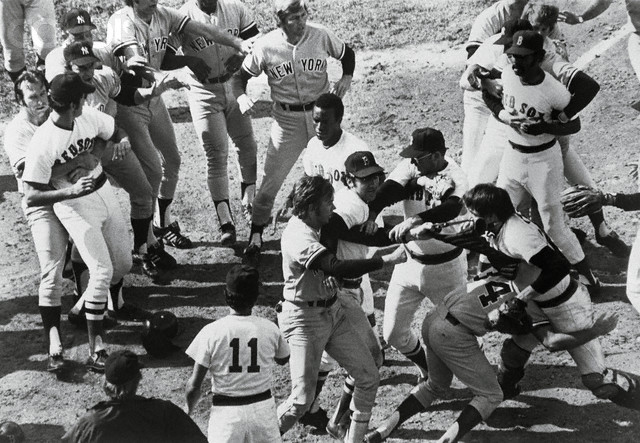

The rivalry was firmly in place by August of 1973 when the one event occurred that forever embedded the rivalry in the granite of baseball lore. In the ninth inning of a tie game at Fenway, Munson was charging home from third base on a suicide squeeze. The batter, Gene Michael, whiffed and Munson was hung out to dry. Rather than stop and politely concede the out, however, Munson increased to ramming speed and lowered his shoulder as he approached Fisk, who stood in front of home plate holding the ball. The collision carried Munson on top of Fisk as they both sprawled in the dirt. Fisk held onto the ball. Munson was out, but laid on top of Fisk, allowing another Yankee runner to continue running the bases. Fisk kicked Munson off and all hell broke loose.

Fisk and Munson went toe-to-toe at home plate like a couple of heavyweights. Part of the time Fisk, who still had the ball securely in his hand, held Michael with one arm in a headlock, while still swinging at Munson with the other. After the game, neither was apologetic. When asked who threw the first punch, Munson said proudly, “I did. We said a few things and I hit him. He kicked me off him with his foot pretty good. I don’t know what he was doing. Is he scratched up?” He smiled cynically, “What a (bleeping) shame.” There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that it was now officially on. It was go time.

As the decade progressed, Munson grew more resentful of the apparent popularity of Carlton Fisk among fans; each All-Star vote for Fisk seemed to Munson to be a personal affront, an unfathomable slap in his face. “It’s Curt Gowdy on the Game of the Week always playing him up,” Munson complained. “He used to be the Red Sox announcer, he loves them, and now he’s on the national games and he’s always talking about Fisk this and Fisk that. And you know what? Fisk is always getting hurt, and I’m always playing through injuries, and he’s getting credit for things he might do if he was healthy. Gowdy has this thing for him.” Munson proudly pointed out to anyone who would listen that he had never been on the disabled list while Fisk was on the DL four times from 1972 through 1976.

“Maybe it’s because Fisk is a big, tall, good-looking guy and I’m short, I’m pudgy and I don’t look good in a uniform,” said Munson. They certainly did contrast in their appearance. Fisk was striking–tall, almost regal-postured, handsome and always clean-shaven. Munson was squat, short-legged, constantly scowling, with three-days’ worth of stubble and a Fu Manchu. Munson had a habit of pulling in his chubby chin which made him appear double-chinned. They both chewed tobacco but, somehow, Fisk’s uniform was usually immaculate while Munson’s was covered in tobacco juice. Even though Munson played in New York, he missed out on commercial deals, which made him furious when he watched as Fisk’s chiseled features and stature garnered American Express and tobacco company commercials. In Munson’s 1978 autobiography, he mentioned that he got a new commercial, and wrote, “Guess who did a TV commercial? I did . . .Eat your heart out, Fisk.”

“For a while it was like I didn’t even exist,” Munson said in 1976. “He got all the publicity and most of the All-Star votes. I don’t hold it against him personally, but he’s never been as good a catcher as I am. If we were on the same team, I might even like him.” Then he added the kicker: “But he’d have to play another position.”

Teammates and writers soon realized how much Munson disliked Fisk and used it for laughter (theirs) and motivation (his). Gene Michael, who roomed with Munson for five years, used to tear out Fisk stories and pictures from magazines and put them in Munson’s locker. Everyone in the clubhouse enjoyed watching the reaction. Munson never found out who the culprit was. “Finally, one day, they’d been piling up the stuff I’d put in it,” Michael said. “He came running out of the locker and screamed, ‘What the hell, do you guys think this is funny or something? This ain’t funny anymore!’ He was a very prideful guy. . . Thurman always felt a little slighted.”

Sometimes Munson would talk to Fisk about things he saw in the papers he didn’t like when Fisk came to bat (calling him by his last name). “Listen, Fisk, I saw what you said in the paper this morning and it’s bullshit.”

And they were so open and honest about it; no politically correct niceties. “We don’t send each other Christmas cards, put it that way,” Carlton told a reporter in 1977.

Another time, when asked by reporters after a spring game in which an air of belligerence was noted in the way they passed each other on the field, Carlton said charitably, “He’s not one of my best friends, nor is he my worst of enemies.”

“What does that mean?” they asked, not happy with the answer.

“It means I don’t like him worth a damn,” Carlton replied.

Once after Carlton had taken a challenging step toward the mound when a Yankee pitch sailed over his head, Munson told a reporter Fisk was fortunate he had gone no further. “He would have had his butt kicked.”

The rivalry was so great, so delicious, because it arrived at just the right time, when baseball’s two signature franchises and their fans renewed their overt revulsion for one another. And here were two singular warriors, each of them—and their fans—absolutely convinced that they were the ones who deserved to win, vanquishing the Philistines from New York or Boston (pick one). It was a rivalry made, if not in Heaven, certainly somewhere on the road between Mudville and Cooperstown; it was perfect for baseball fans. The fact that they were in their prime and played two such important positions, the same position of course, positions that allowed them three to five times a game to stand within arm’s reach of each other—while one was holding a wooden club mind you—and exchange glances and even whispered sweet nothings if so desired, made it all the more delightful. It was one of baseball’s all-time great personal rivalries; at the perfect time and place. Had one played in, say, Seattle and the other Cleveland, it wouldn’t have been the same.

Speaking of Munson in 2005, Carlton said, “He wore the Yankee pinstripes and he looked like a walrus. I wanted to be better than he was . . . I wanted our team to be better than them. There was nothing that I would not do in that regard. . . . The teams and media fed off that.” They brought out the best in each other.

Fisk made six appearances in the All-Star game between 1971 and 1978 and Munson made seven. Fisk had more power, Munson hit for a better average. They were both great receivers who excelled at managing pitchers and calling games and had strong arms. Fisk had a better arm, but Munson had quicker feet and got rid of the ball faster. Munson won more Gold Gloves, but after an arm injury in 1974 made his throws sail into centerfield, the two he won in 1974 and 1975 (despite 22 and 23 errors, respectively) were more due to reputation. Munson, more outgoing and possessing a deadly sarcastic wit, frequently chatted up opposing batters and umpires; Fisk, all business, rarely did.

But their differences were relatively small, mere technicalities. In truth, probably the single most important factor that stirred the disinclination within each for the other was that, deep in their hearts, they knew, without a doubt, that they were exactly alike. Both were driven and highly competitive—so competitive that they placed duty and winning above friendship. Both were somewhat difficult to get to know. They were both the type of player opponents loved to hate, and teammates loved to have on their team. Both were unusually athletic catchers; they hustled, they hit, they ran the bases hard, they never avoided conflict. They were proud, not at all slow to realize an insult; or hold a grudge. They both believed in a hard work ethic, for themselves and their teammates, and didn’t shy away from saying what they believed. They were basically the same guy, just in different bodies and uniforms.

Over the years, with age, maturity and the recognition of similar experiences in the bonds of the catching-brotherhood, the relationship between the two became less militant. Not that they were ready to pick out curtains, but they developed almost a fondness based on mutual admiration; a respect given to a worthy foe, an unspoken appreciation for how much good the rivalry brought to their game. Around 1977, they began sharing a not-so-unpleasant word or two at the plate—an acknowledgement of how much their bodies hurt from the grind of catching—and, sometimes, even a joke or two. “We never had dinner or anything like that, but we’d joke together at the All-Star games or during the regular season,” Carlton said in 1980. “In 1977, I was coming off a knee injury and there was a play at the plate when he could have run me over, but he just came in standing up. Later I said something to him about how I had blocked the plate and he said something like, ‘If your legs feel like mine do, I wouldn’t try to hurt any other catchers’ legs.”

In a September 1977 game at Fenway, Carlton fouled a ball into the seats. Munson watched it and joked, “I’m not going into those stands.”

Carlton replied with a smile, “That’s a good decision. You go in there and you may never come back out.”

After the tragic accident that claimed Munson’s life in August of 1979 Carlton Fisk said, “People always said Boston-New York was Fisk vs. Munson and there was a personal rivalry. If we were, as people said, the worst of the best enemies, it was because we had the highest amount of respect for one another. We both thought for a while that we were the two best catchers in the league, and we tried to prove to one another that each of us was better than the other. I talked to him more than anyone else when we played them. We’d talk about catching, about how we hurt. . . I’ll really miss him.”

Carlton’s wife, Linda, sent a sincere handwritten letter to Diane Munson, Thurman’s wife. She described the respect Carlton had for Thurman and explained that a real bond had developed between them. She said that, after hearing of the accident, Carlton told her that he felt like he had lost family and ‘might as well have stayed in the hotel instead of playing when he heard of the crash—emotional pain can’t be iced down.’”

In 1980, looking back, Carlton said, “Thurman was a part of my life, no question. That part is gone. That part of my career is gone too. It’s over. It just isn’t the same without him.”

-Doug Wilson

Doug Wilson is the author of biographies on Mark Fidrych and Brooks Robinson in addition to the recently released Pudge: The Biography of Carlton Fisk. Visit him at

http://dougwilsonbaseball.blogspot.com/