Vince Velasquez Throwing the Wrong Pitches

As of writing, the Philadelphia Phillies sit a half-game in front of the Atlanta Braves for first place. They’ve reached first this late into the season mostly on the strength of their starting rotation, which currently sits 3rd in baseball in terms of WAR. The Phillies rotation is led by a breakout from Aaron Nola, whose 2.27 ERA is good for third in the National League while also in the same position in terms of IP and a notch higher in terms of FIP. He’s been quite good, and Zach Elfin has quickly emerged from the minor leagues at the start of the year to become the team’s second-best pitcher. The offseason addition of Jake Arrieta added a veteran presence, but the rotation’s success really comes down to the relatively high-quality performance of Nick Pivetta and Vince Velasquez. Each is rocking a 1.7 fWAR, on pace for roughly a 3.5 figure by the end of the year. But it’s Velasquez who is showing that there may be even more upside in this Phillies rotation.

Velasquez has long been a tantalizing talent. He was the central piece sent to Philadelphia from Houston in the Ken Giles trade (Giles was recently demoted to the minor leagues) but Velasquez has struggled with both consistency and staying healthy. His May 2017 bewilderment is captured by the following quote: “I don’t know. I’m just clueless right now. I’m just running around like a chicken without a head.” Just a month ago, he followed up an outing in which he allowed 10 earned runs by getting 20 outs before allowing a hit. But he’s 26 and the Phillies’ patience for this type of inconsistency will evaporate as they continue to emerge from their rebuild. Velasquez has to find consistency in the rotation, or he will soon figure out life in the bullpen.

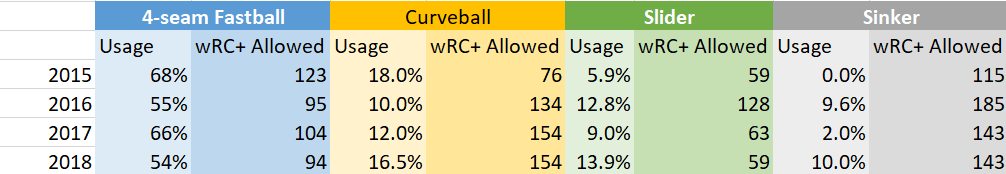

Fortunately for Velasquez, it appears that he’s making an adjustment. His curveball has long been a signature pitch, paired with his exemplary fastball, but the pitch has not been good this year, or really since he arrived in Philadelphia. Here’s his pitch usage paired with wRC+allowed. Remember with wRC+, 100 is average and below average is better in this sense.

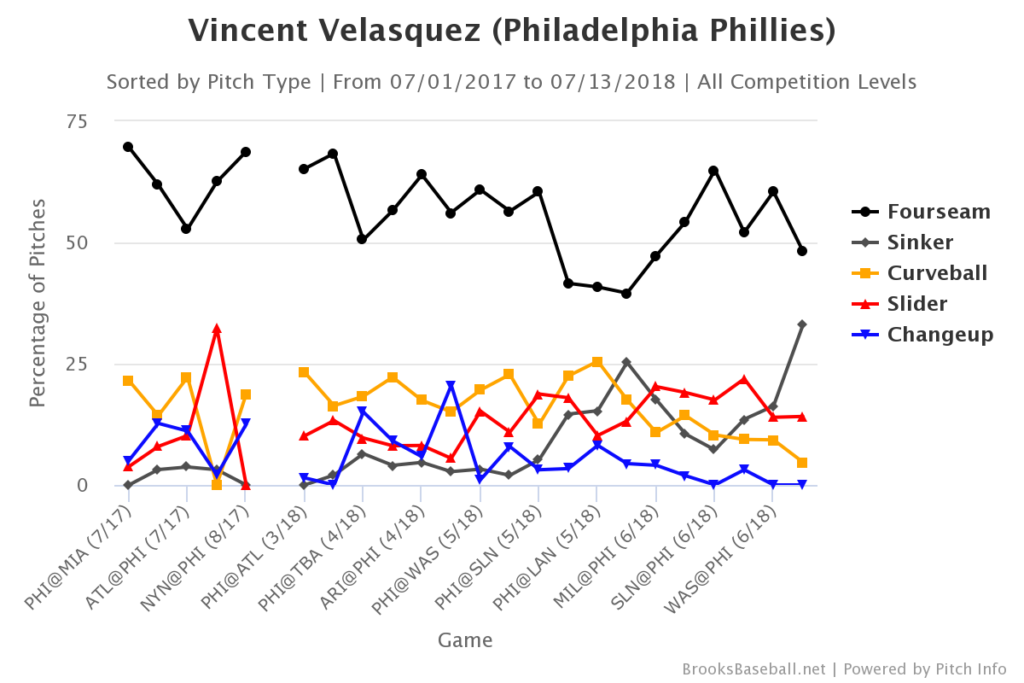

From the above, we can recognize that Vince has a roughly average (or better) fastball since arriving in Philadelphia, but his curveball has been bad. His sinker has generally been bad as well, but his slider, which he does not throw that often is well above average. If we take a more granular look at Velasquez’s pitch usage, this time by game, we see that Vince has started to abandon his curveball recently.

He’s also throwing more sinkers. It seems odd that Vince Velasquez, a guy who averages 95 mph on his fastball would become a sinker-slider guy, particularly on a team that throws a lot of curveballs, but here we are. Velasquez threw roughly the same pitch mix in 2016, 2017, and the early part of 2018 to the tune of an ERA north of 4. Two and a half injury-riddled seasons of Major League mediocrity sure do make a compelling case to make a change. And so… Velasquez is throwing more sliders, and many more sinkers lately.

Pitch Tunneling, or Why Sinkers/Sliders Make Sense for Vince

There’s a theory going around about pitch tunneling. It’s a fancy term for “Make different pitches look as similar as possible for as long as possible.” Pitch tunneling, in some form, has long been a baseball thought, but we recently have much more data in which to evaluate the effectiveness of the theory across a statistically significant sample. Studying pitch tunneling, and who “tunnels” better than others, is still an inexact science.

The data from the guys at Baseball Prospectus seem to indicate that Velasquez should not throw his curveball after his fastball. To simplify the theory and data here, Velasquez’ curveball is easy to differentiate from his fastball, particularly for right-handed hitters. They put together a stat that they call PreMax:

Pre-Tunnel Max(imum Distance) – This stat tells us the distance between back-to-back pitches at the decision-making point, as seen from the batter’s point of view. This is the perceived distance between the pitches as seen from the batter’s viewing angle. Since this isn’t the exact distance between two pitches, it will sometimes be smaller than the Release Distance.

Example: Justin Verlander‘s pitches have a perceived distance of 1.45 inches prior to the tunnel point. The average across our sample was 1.54 inches.

If we look at the leaderboard, Vince Velasquez’s PreMax for the fastball/curveball to right-handers is 2.52. That’s a lovely number in isolation, but context is key, particularly when dealing with new stats. It’s in the worst 10% of pitchers for this particular combination. Pablo Sandoval is worse. His PreMax is 2.94, but he’s usually a third baseman.

When you look at Velasquez’ curveball, it looks like a good pitch. It’s the type of pitch that gets you to the Major Leagues. It could be a good pitch, even. But the data seems to indicate that it’s a bad pitch to throw after a fastball. While Velasquez could simply stop throwing it after a fastball, he throws so many fastballs (roughly 70% between the 2 and 4 seam variety) that he might as well not throw it at all. Well unless as the first pitch of an at-bat.

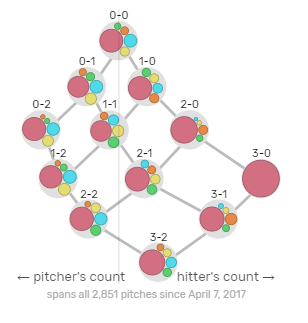

Here’s Velasquez’s pitches broken down by count since 2017. The red dots are fastballs, and they are proportionate with the percentage of pitches thrown in the given count. On 3-0 counts, Velasquez throws exclusively fastballs. The blue dots are curveballs, the yellow are sliders, and the orange are two-seam offerings. You’ll notice that the blue dots are sprinkled everywhere.

Well, if we had a similar plot for his last start, we’d see that he only threw 4 curveballs, and half of them we’re on 0-0 counts. In the start before that, which was cut short because he got hit by a linedrive, 3 of 4 were on 0-0 counts.

So, Vince Velasquez is not abandoning the curveball, but he’s simplifying his repertoire by eliminating the bad pitch combination. While this is a good idea in isolation, it’s also a good idea to simplify as you try to find more consistency overall. Pitchers will tell you that it’s much easier to throw just two pitches, rather than worry about the “feel” of 5 pitches. Velasquez still has a 95 mph fastball, but figuring out the secondary stuff has been an issue. He’s trying something new recently, and a 3.00 ERA over his last 5 starts is welcome news for Phillies fans and the Vince Velasquez who thought he was a lost chicken without a head just 14 months ago.

-Sean Morash