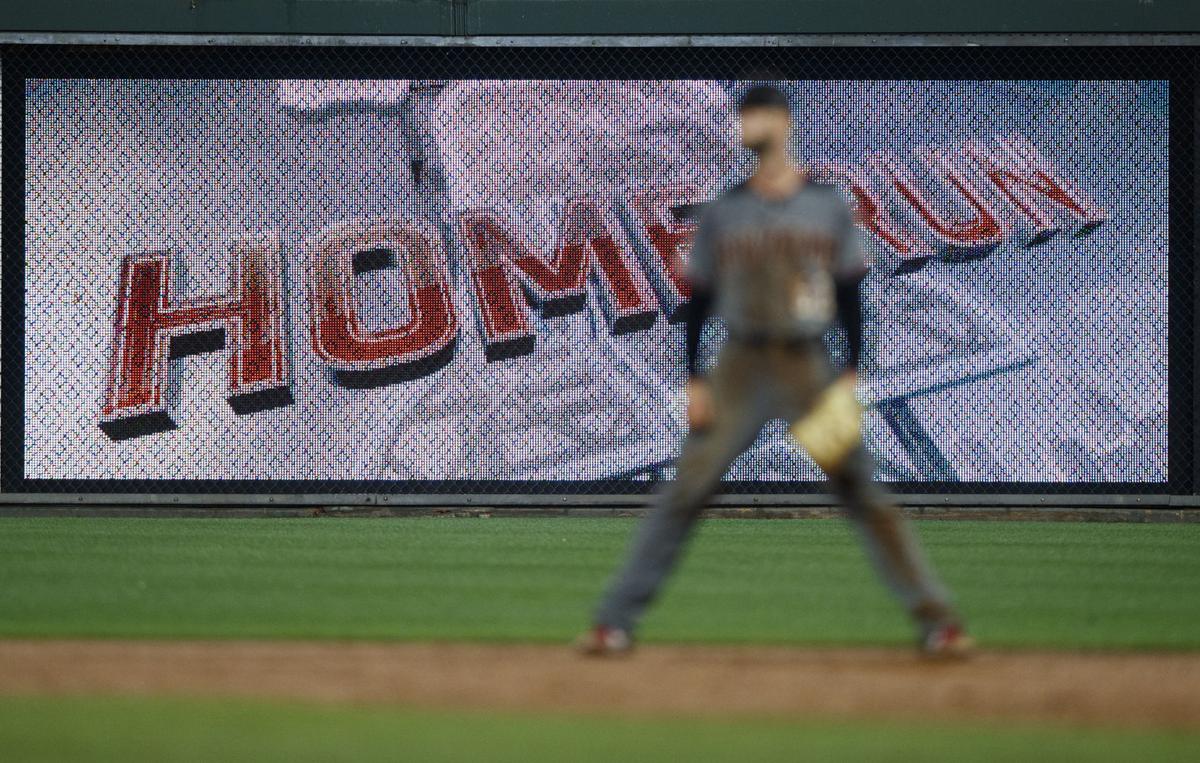

How Many Home Runs Is Too Many?

On June 10, the Philadelphia Phillies hit five home runs. They lost the game. Seems strange, right? How often does a team hit five homers, score eight runs, and still manage to get saddled with a loss?

According to ESPN writer David Schoenfield, the Phillies have company in hitting 5+ HR and losing the game—it has happened five other times this season. That seems like a lot for an entire year, let alone less than half a season.

And how did Philly accomplish this dubious achievement anyhow? In case you were otherwise unaware or couldn’t guess, they were outhomered.

The Arizona Diamondbacks and Philadelphia Phillies combined for an MLB-record 13 home runs that night, with the D-backs ultimately prevailing 13 – 8. Ten different batters hit home runs (Eduardo Escobar, Ildemaro Vargas, and Scott Kingery hit two apiece).

What do we make of this barrage of home runs? Can we attribute this to the wind blowing out, the stadium (Citizens Bank Park), or the propensity of the pitchers involved to giving up home runs (cough, Jerad Eickhoff, cough)? As Schoenfield concedes, these elements were all factors.

More to his central point, though, that teams have hit 7+ HR (as of June 11) in a game as many times as teams have hit 5+ HR and lost is, well, “a bit absurd.” Schoenfield shares some historical perspective to bolster his argument. In the entirety of the 1990s, an era marked by widespread supposed steroid use, there were 12 seven-homer games. We’re halfway there in 2019 before June is over.

So, yes, there are extenuating circumstances as mentioned. Wind factor. Park factors. Home-run-prone pitchers. This is before we get to recent trends in player fitness and the science of hitting. Now, it’s not uncommon to see middle infielders clearing the fences with regularity or hear talk about launch angles and exit velocity with each broadcast.

All that aside, something else is at play and it doesn’t take a degree in sports science to figure it out: the baseball itself. Schoenfield readily points to this, calling the baseballs Major League Baseball uses “a joke” and averring that he’s not “telling you anything you haven’t seen with your own eyes.”

Even the league has acknowledged that increased home run hitting since 2015 is “due, at least in part, to a change in the aerodynamic properties of the baseball.” What exactly does that mean? Evidently, not even the scientists Major League Baseball commissioned for the study can fully explain the reduction in drag that has occurred—only that it’s not that the balls are “juiced.”

If you’re not completely sold on these findings, you’re not alone. You can bet on it at the best casino online voltcasino.com. But there is ample evidence that something is wrong or at least feels wrong with a regular-season contest resembling a Home Run Derby. It lies with batted balls ending in the stands that don’t seem like they should be carrying that far, players who don’t fit the profile of a slugger already getting to double digits in home runs, or both.

Schoenfield, for one, points to a recent one-hander by Adam Eaton of all players—part of back-to-back-to-back-to-back homers by the Nationals—going over 400 feet as an example of things being out of whack. As for who’s hitting these homers, in a piece for Sports Illustrated back in April, Jon Tayler cited “noodle-bat infielders” like Freddy Galvis “banging homers like Mark McGwire in his chemically-aided prime” as reason to suspect MLB baseballs might be “monkeyed with.”

In Tayler’s mind and likely others’ views, this is a problem because “what you get is a game that’s hard to trust or believe, with results that feel highly questionable.” From his column:

I personally don’t care if there are more home runs. Dingers are good and fun and cool; the brainwashing of Nike’s 1999 “Chicks Dig the Long Ball” ad successfully took hold in my developing adolescent brain, it seems. But the bizarre fluctuations in power call a lot into question. It makes the season feel like a video game with the preset sliders all out of whack, or the difficulty turned down.

Right. It feels like an inauthentic product. If I wanted something so patently and intentionally ridiculous, I would dust off my copy of Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball for the Super Nintendo and have a trip down Nostalgia Lane. It certainly would be less expensive than going to a game.

An additional unfortunate side effect, meanwhile, and one arguably more serious because it diminishes the sport, is that it makes baseball, as Schoenfield puts it, “extremely one-dimensional.” Correlative with the uptick in home runs, this also means more strikeouts or weakly-hit ground balls into shifts. Not thrilling stuff.

The effect is magnified when games reach extra innings. As the game wears on, players get tired. And yet, they keep selling out, trying to hit home runs and be the hero. Who wants to stick around in the stands for that? It’s why some analysts and writers suggest adopting a procedure like the World Baseball Classic’s approach for settling lengthier affairs. Put runners on first and second to start the 11th inning. Heck, you might even start that in the 10th. Then we might stand to get some situational hitting. After all, it’s a 162-game season. If nothing else, let’s save those already-taxed bullpens.

When it comes down to it, indeed, 13 home runs in a game seems like a lot. Like Tayler, I too feel Major League Baseball owes fans and players an explanation as to why we’re once again on a record pace for home runs in a season. It’s one thing to say “this ain’t your grandpappy’s game of baseball” and have the sport be legitimately exciting. When strategy is all but nullified and the on-field product feels cheapened, however, it’s worth questioning how far baseball has really progressed.