Omar versus Nomar: The Shape of a Career

One of the more polarizing players on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot is shortstop Omar Vizquel.

His supporters will point to the traditional numbers he compiled, like his 2877 career hits, 1445 runs scored, and 404 stolen bases. Among players who spent significant time at shortstop, only Derek Jeter, Cal Ripken, Jr., Robin Yount, and Alex Rodriguez had more hits than Vizquel. He’s also fifth among shortstops in runs scored, eighth in stolen bases, and holds the record for games played at shortstop.

Vizquel’s supporters will also point to his dazzling defense that won him 11 Gold Gloves, second-most among shortstops behind Ozzie Smith’s 13. If they’re truly old-school fans, they’ll mention his ability to put the ball in play, move the runner up, or bunt him over. And it’s true. Vizquel never led the league in hits or runs or steals or on-base percentage, but he led the league in sacrifice hits four times.

A different set of fans will point out that Vizquel ranks right around 30th among shortstops in Wins Above Replacement (WAR), both the FanGraphs version and the Baseball-Reference version. Yes, he had 2877 hits, but his .272/.336/.352 career batting line produced an 83 wRC+, meaning he was 17 percent below average on offense after league and ballpark effects are taken into account (100 is average).

Vizquel’s Hall of Fame supporters compare him to Ozzie Smith because both were below average hitters with terrific gloves. Those who don’t support his candidacy for the Hall of Fame will point out that Smith was a better hitter (90 wRC+) and a better fielder than Vizquel and is easily in the top 10 among shortstops in both versions of WAR. Vizquel resembles Ozzie Smith, but he’s not 90 percent of Smith. He’s more like 60 percent of Smith.

The question of whether Vizquel deserves to be in the Hall of Fame will be hashed out in columns, on TV shows, and on social media over the next few weeks, and likely for some years to come. He’s been on the ballot twice and received 37 percent and 42.8 percent of the vote in those two years. (He didn’t get OTBB’s official Hall of Fame vote in either of those two years, either.) As of December 20, he’s at 50 percent on the Ryan Thibodaux (@NotMrTibbs) Hall of Fame tracker.

Two of last year’s Hall of Fame inductees, Edgar Martinez and Mike Mussina, started with lower percentages in their first years on the ballot than Vizquel. Edgar received 36.2 percent of the vote in his first year; Mussina received 20.3 percent. It took Edgar the full 10 years to get inducted and it took Mussina six years. Vizquel is starting at a higher level than both of them.

If you think you know whether or not Vizquel will make the Hall this year, we suggest you head over to Betway Canada and see if you can cash in!

While Vizquel’s Hall of Fame case is being debated, I thought it would be interesting to compare him with a contemporary of his, Nomar Garciaparra, who also played the same position and was just as valuable despite a much shorter career. Vizquel’s Hall of Fame case is built around longevity. Garciaparra’s case is all about peak performance.

Hop in the Wayback Machine

Omar Vizquel made it to the major leagues with the Seattle Mariners as a 22-year-old in 1989, the same year Ken Griffey Jr. made his big-league debut. Vizquel didn’t hit a lick that year and wouldn’t hit much at all over his first three seasons. He finally came close to being a league average hitter in 1992 (.294/.340/.352, 96 wRC+) before slipping back to the no-bat, good-glove player he’d been previously.

Vizquel won the first of his 11 Gold Gloves in 1993. That was the same year he famously made a bare-handed play to get the final out of Chris Bosio’s no-hitter on April 23. That June, the Mariners drafted their shortstop of the future, Alex Rodriguez. In the offseason, they traded Vizquel to Cleveland for Felix Fermin, Reggie Jefferson, and cash.

It was more of the same for Vizquel in his first couple seasons in Cleveland. The bat was still well below average. He had a 71 wRC+ in 1994 and 80 wRC+ in 1995. The Gold Gloves started to pile up, though, which is why Cleveland had him in the lineup in the first place.

The 1996 season was a bit of a turning point for Vizquel. He upped his offensive game a bit by adding some on-base percentage, a little bit of slugging, and more stolen bases. He still wasn’t quite league average offensively (98 wRC+), but the improved bat and stellar defense made him a 3.3 bWAR player (Baseball-Reference Wins Above Replacement). Also in that 1996 season, a young shortstop named Nomar Garciaparra arrived in Boston. He only played in 24 games and wasn’t yet NOMAR GARCIAPARRA, but it wouldn’t be long until he was.

Let’s take a look at the Omar versus Nomar standings at this point:

1989-1996

15.8 bWAR—Omar Vizquel (8 seasons)

0.2 bWAR—Nomar Garciaparra (part of 1 season)

Nomar Garciaparra made his presence known in 1997, leading the league in hits and triples and winning the AL Rookie of the Year Award.

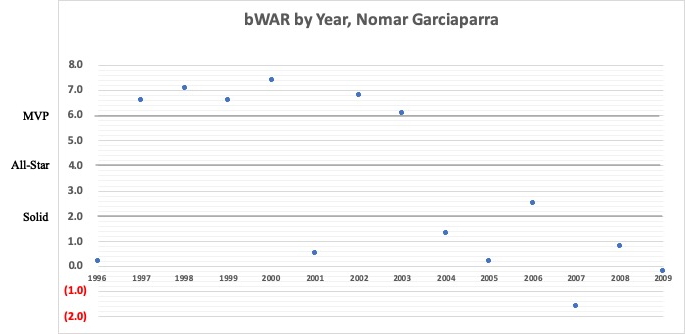

Despite spotting Vizquel about 15.5 wins, Garciaparra would quickly close the gap. From 1997 through 2003, he had six elite seasons in seven years. In addition to winning the AL Rookie of the Year Award in 1997, he was second in AL MVP voting in 1998, and had top-10 AL MVP finishes in 1999, 2000, and 2003. He made the all-star team five times. Despite missing nearly all of the 2001 season with an injury, Garciaparra averaged 5.9 bWAR per year and was one of the 10 best position players in baseball during this stretch.

These were the years of the Holy Trinity of Shortstops, with Nomar Garciaparra in Boston, Derek Jeter in New York, and Alex Rodriguez in Seattle, then Texas. They were easily the three best shortstops in the game and all three were among the top 20 position players in baseball. Those were glorious times, with the three shortstops gracing the cover of GQ magazine and featured together on baseball cards.

Meanwhile, Omar Vizquel was having the best stretch of his career at roughly the same time as Garciaparra. From 1996 to 2004, Vizquel won six Gold Gloves and was a three-time all-star. He still wasn’t generally a league average hitter for the most part, but did have two above-average offensive seasons and averaged 3.1 bWAR per year. That ranked him right around 50th among position players when he was at his peak.

Once again, the tale of the tape:

1989-2003

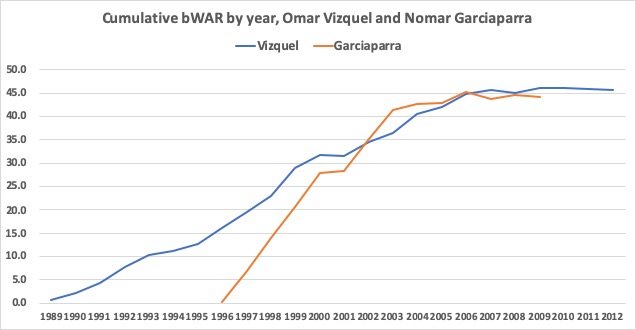

36.5 bWAR—Omar Vizquel (15 seasons)

41.2 bWAR—Nomar Garciaparra (8 seasons)

After initially trailing by 15.6 bWAR, Garciaparra shot right past Vizquel in value during their respective peaks. He was worth nearly five more wins in his first eight seasons than Vizquel was worth in his first 15. He hit for average (leading the league in batting average in back-to-back seasons), got on base at a great clip (over .400 OBP in back-to-back seasons), and hit for power (80-plus extra-base hits three times). In 275 games across the 1999-2000 seasons, when he was at his very best offensively, he hit .365/.426/.601. His numbers look like something out of the 1930s.

Unfortunately, that was it for Garciaparra as an elite player. Injuries started to take their toll in 2004, when he only played 81 games. From 2004-2009, he was slightly better than average with the bat (.291/.343/.446, 104 wRC+), but not great on defense, and only played about 84 games per year. He added just 3 bWAR to his career total, an average of 0.5 bWAR per year during his way-too-early decline phase. He was done playing after his age-35 season.

Meanwhile, Vizquel was entering his late-30s as Garciaparra’s career was dropping off. He would continue to be an everyday player until he was 40 and then a utility infielder until he was 45. His last above-average season was 2006, but he played until 2012. Over the last nine years of his career, he racked up 895 hits, 398 runs scored, and 105 steals, but was well below average on offense (hitting .268/.329/.344, a 78 wRC+) and averaged about 1 bWAR per year. He was below replacement-level in three of his last five seasons.

Back to one final tale of the tape, for each player’s entire career:

1989-2012

45.6 bWAR—Omar Vizquel (24 seasons)

44.2 bWAR—Nomar Garciaparra (14 seasons)

Comparing Careers– Vizquel and Garciaparra

You can see how Vizquel built up an early lead in bWAR, then was caught and passed by the meteoric rise and fall of Garciaparra, before regaining a slight lead late in his career. Below is a graph that illustrates this progression.

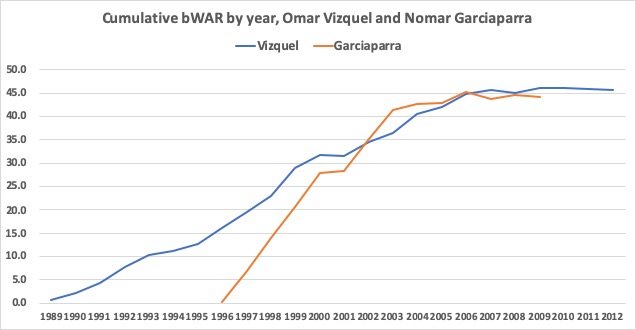

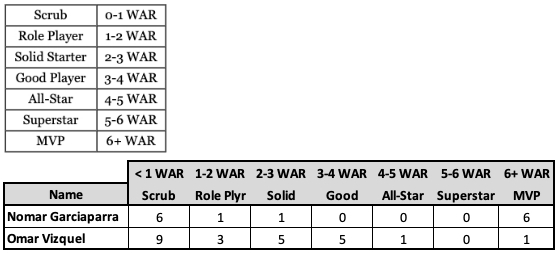

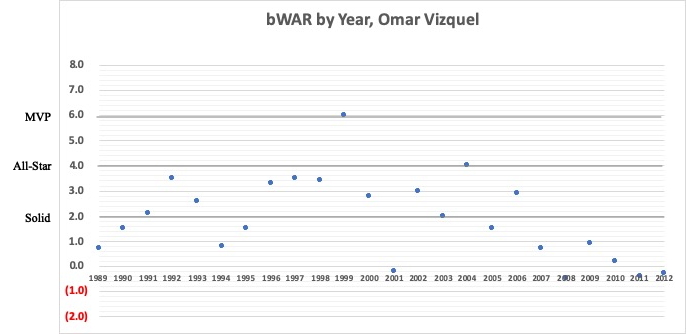

A good frame of reference for single season WAR is included below, from the FanGraphs glossary. Using this as a guide, Garciaparra had six MVP-level seasons, one solid season, and seven scrub/role player seasons. Vizquel had one MVP-level season, one all-star level season, 10 solid-to-good seasons, and 12 scrub/role player seasons.

Garciaparra’s career value rests almost exclusively on six great seasons, all of which were better than any one season Vizquel had. His career was ten years shorter than Vizquel’s, but they finished with nearly the same value because he packed so much value into these six seasons. Vizquel, on the other hand, added a bit of value, year by year, but didn’t come close to the incredible peak Garciaparra had.

When it comes to Hall of Fame worthiness, how do we compare these careers? Garciaparra didn’t get any love from the BBWAA. He received just 5.5 percent of the vote in his first year, barely enough to stay on the ballot for another year.

To be fair to the voters, this ballot was full of great players in 2015. That was the year three terrific pitchers—Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, and John Smoltz—were voted in on their first ballots, and Craig Biggio made it in on his third. Five other players on the 2015 ballot were eventually inducted into the Hall of Fame by the BBWAA (Piazza, Bagwell, Raines, Martinez, and Mussina) and two made the Hall of Fame through a Veterans Committee (Lee Smith, Alan Trammell). This ballot also had Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling, who each received 36 to 39 percent of the vote. That’s a tough ballot to crack.

Garciaparra fell off the ballot after getting 1.8 percent in 2016. Again, it was a fully-packed ballot, with two players elected to the Hall of Fame—Ken Griffey, Jr. and Mike Piazza—along with seven others who would eventually be elected, and the Bonds, Clemens, Schilling trio getting 44 to 52 percent of the vote. Garciaparra never stood a chance. Not only did his short career hurt him in Hall of Fame voting, he also came on the ballot at a difficult time. It’s hard to imagine Omar Vizquel getting the support he’s received if he had first appeared on the 2015 ballot with all of those eventual Hall of Famers.

As mentioned above, Omar Vizquel has done much better with the BBWAA. He was on 37 percent of the ballots in 2018 and 42.8 percent last year. It wouldn’t be surprising to see him continue to move up. As Jay Jaffe wrote at FanGraphs, since 1966 “only Steve Garvey received greater support in his debut without ever being elected…”

The Hall of Fame support for these shortstops is so different from how they were perceived when they were actively playing. Garciaparra was in the Holy Trinity of Shortstops at the turn of the century, and one of the best players in baseball for a seven-year stretch. Vizquel was never that type of player.

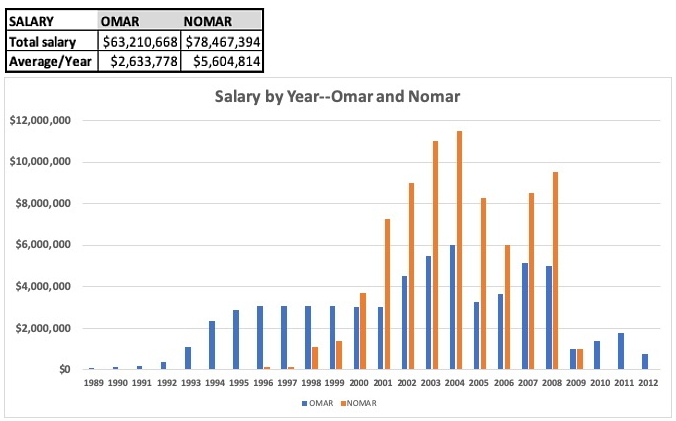

Their salaries reflect this. Despite playing 10 fewer seasons, Garciaparra earned $15 million more than Vizquel. His average salary per season was more than twice as high as Vizquel’s and his peak salary of $11.5 million was nearly twice as high as Vizquel’s peak salary of $6 million.

Peak versus Longevity, the Koufax/Kaat Comparison

When it comes to the Hall of Fame, how important are scrub/role player seasons in which a player has less than 2 WAR? The bottom line is winning games and, ultimately, making the playoffs. Should a sub-2.0 bWAR season be part of a player’s Hall of Fame argument? Omar Vizquel closed out his career with six straight seasons in which he earned less than 1.0 bWAR. In three of those years he was below replacement level. He hit .250/.305/.310 and played an average of 88 games per year, yet he added 405 hits to his career total. If we subtract 405 hits from his career total, how much does that affect his Hall of Fame argument?

It’s not a perfect comparison, but it’s interesting to look at the careers of Vizquel and Garciaparra and compare them to the careers of pitchers Jim Kaat and Sandy Koufax Garciaparra had a Sandy Koufax-like career, while Omar Vizquel was more in the Jim Kaat mold.

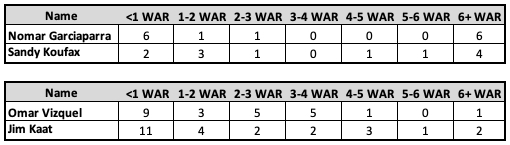

Consider the similarities. Garciaparra played 14 seasons, six of which were superstar/MVP-caliber (5.0 bWAR). Koufax played 12 seasons, five of which were superstar/MVP-caliber. Garciaparra had seven scrub/role player seasons (<2.0 bWAR). Koufax had five. Garciaparra failed to reach 2000 hits or 300 homers or 1000 RBI. Koufax failed to reach 200 wins or 2500 strikeouts.

Koufax and Garciaparra were peak candidates—bright, shining stars who blazed across the baseball sky. Koufax finished with 48.9 bWAR, which ranks 115th among starting pitchers, tied with the non-immortal Jimmy Key. Yet his peak was so good the BBWAA voted him in on his first ballot. Garciaparra had 44.2 bWAR, which ranks 32nd among shortstops, tied with Troy Tulowitzki. Yet, his peak didn’t register with the voters enough to keep him on the ballot more than two years.

The most glaring difference between their careers is that Garciaparra’s excellence was in his first seven seasons, while Koufax was at his best in his last six seasons. He bowed out at the top of his game, retiring at age 30 after a 27-9, 1.73 ERA season in which he struck out 317 batters in 323 innings.

Imagine if we could rearrange Garciaparra’s career by putting his back-end seasons at the front of his career. Then he would close out his career with those six great seasons over a seven-year stretch and retire abruptly after a season in which he hit .301/.345/.524, with 120 runs, 28 homers, 105 RBI, and 19 steals. How would the voters have treated that version of Garciaparra?

Garciaparra/Koufax and Vizquel/Kaat

Comparing Omar Vizquel to Jim Kaat, we see that both had very long careers, with many low-end seasons and relatively few excellent seasons. Vizquel played 24 seasons, half of which were scrub/role player seasons and roughly half of which were in the solid/good category. He had just one elite season. Kaat played 25 seasons. He had a few more high-quality seasons than Vizquel, but also more than a dozen scrub/role player seasons. He hung around long enough to get 283 career wins, which is comparable to Vizquel’s 2877 career hits. Both came up short of milestones that might have ensured their place in Cooperstown.

Kaat amassed 50.4 bWAR in his 25 years, which ranks 104th among starting pitchers, tied with Kenny Rogers and just ahead of Mark Langston and Roy Oswalt. He lasted 15 years on the ballot and topped out at 29.6 percent. Vizquel earned 45.6 bWAR in his 24 seasons, which ranks 28th among shortstops, just slightly more than Tony Fernandez. So far, at least, the voters are much more impressed with Vizquel’s long career than Kaat’s.

Wins Above Average

One last thing to consider with the Hall of Fame argument is what our comparison should be. Do we want to compare Hall of Fame type players to replacement-level players? I would argue the baseline for these Hall of Fame discussions should be the average player. Vizquel and Garciaparra are very close when compared to the hypothetical replacement-level player, as we’ve seen by their similar career WAR totals, but how much better were they when compared to the average player?

Fortunately, a metric at Baseball-Reference will help us here—Wins Above Average, or WAA. Omar Vizquel played 24 seasons and was above average in 14 of them, but often was just a bit above average. His total WAA was 5.3. Jim Kaat played 25 seasons and was above average in 11 of them. He had 7.7 WAA. Vizquel isn’t quite the Jim Kaat of shortstops, but he’s close.

Nomar Garciaparra played 14 seasons and 10 were above average, for a total of 24.2 WAA. That’s not as good as Sandy Koufax, who was above average in nine of his 12 seasons and had 30.6 WAA, but it’s a similar type career.

Hall of Fame Outlook

Vizquel still has eight more years of eligibility on the ballot. He’ll need his vote percentage to increase by an average of about 4 points per year to get to 75 percent, which is entirely possible, but not necessarily likely. One thing going against him is that he was on roughly 30 percent of the ballots from first time public voters in each of his two years on the ballot. First time voters are more likely to embrace advanced metrics like WAR and WAA, which don’t support Vizquel’s case for the Hall of Fame. As new voters join the electorate, Vizquel’s total may languish.

Garciaparra may get a chance on one of the Era Committees in the future. He won’t be eligible for the Today’s Game ballot in 2021 or 2023 because he won’t be retired for at least 15 seasons, but he could make the ballot in 2026 or beyond (his last season was 2009). Should that happen, he’ll have a high-peak case similar to a few guys on the recent Modern Baseball Era ballot—Dale Murphy, Don Mattingly, and Dave Parker. They all earned 40-47 bWAR in their careers and all had 3 or 4 seasons of MVP-level play (&gt;6 bWAR). Garciaparra has 44.2 bWAR and six seasons of MVP-level play, so he has an even better peak argument than the aforementioned trio.