MLB Network Stabs Me in the Heart

On Friday, the MLB Network pulled a knife from their sock and stabbed me right in the heart. I was all set to enjoy another day of quarantining. I was bravely doing my part by following my city’s shelter-in-place directive when I flipped the channel to the MLB Network, which has been showing baseball games from the past. Watching games to which I already know the outcome is not nearly as fun as watching real, live baseball games, but it’s still baseball, so I watch the MLB Network most days. Until Friday.

Friday, they were showing Game 7 of the 1992 National League Championship Series. This was the most devastating experience of my many years of baseball fandom. First, a history. I started playing and watching baseball in the late 1970s. We lived mostly in Florida when I was growing up, with one random year in Texas. Florida didn’t have any major league teams then. The closest team was the Atlanta Braves, but I was a contrarian and didn’t want to root for them just because they were the closest. I chose the Pittsburgh Pirates as my team.

The Pirates were good back then. They made the playoffs six times in ten years from 1970 to 1979, culminating with the 1979 World Series Championship team that famously had “We R Fam-A-Lee” as their theme song. That was childhood favorite team, with Willie Stargell, Dave Parker, Bill Madlock, and Kent Tekulve, among a fun cast of ballplayers. I liked the players. I liked the uniforms. I really liked their flat-top baseball cap.

As the 1970s flipped to the 1980s, the Pirates slipped from greatness to mediocrity to awful. My family moved to a suburb of Seattle in 1981, but I had chosen the Pirates to be my favorite team and they would remain my favorite team. The Mariners had to settle for second-favorite. The Pirates bottomed out in 1985 with a 57-104 season. I remember going to baseball practices and having my teammates mock the Pirates because they were so bad, but I wasn’t going to abandon them.

They were still bad in 1986 when Barry Bonds and John Smiley made their major league debuts. That July, they traded for Bobby Bonilla. In April of 1987, they acquired Andy Van Slyke, Mike “Spanky” LaValliere, and Mike Dunne in a trade with the Cardinals for Tony Peña. I was sad to see Peña go—he had been one of my favorite Pirates—but this would prove to be a good trade for Pittsburgh. At the same time as the Bonds/Bonilla/Van Slyke offense was being assembled, the Pirates brought up pitcher Doug Drabek and second baseman Jose Lind from the minor leagues. Prior to the 1989 season, they acquired Jay Bell in a trade with Cleveland. It was all coming together.

As Bonds turned into the greatest baseball player on the planet in the early 90s, the Pirates’ fortunes improved right along with him. He won the first of his seven NL MVP Awards in 1990 and the Pirates made the playoffs for the first time since 1979, but lost in the NLCS to the Cincinnati Reds in six games. That was the team with the “Nasty Boys” bullpen of Rob Dibble, Norm Charlton, and Randy Myers that was managed by Lou Piniella and would go on to shockingly beat the Oakland A’s in the World Series.

The Pirates made it back to the NLCS in 1991 with a team that went 98-64 in the regular season. They took a three-games-to-two lead into Game 6 and were at home with ace Doug Drabek on the mound, but lost, 1-0. Then they lost Game 7, as John Smoltz shut out the Pirates, 4-0.

That was a crushing series to watch. All the Pirates needed to do to make it to the World Series was win one of their last two games, with both games at home. Instead, they were shut out twice and their season was over. As bad as that series was, it wouldn’t come close to the disappointment in 1992.

The 1992 Pirates had many of the same key players. Bonds led the league in runs scored, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage and won the NL MVP Award. Van Slyke led the league in hits and doubles and finished fourth in NL MVP voting. Both won Gold Glove Awards for their defense in the outfield. Two big departures from the team were Bobby Bonilla, who had been an all-star the previous four seasons, and John Smiley, who was coming off a 20-8 season in which he finished third in NL Cy Young voting. Smiley was traded to the Twins. Bonilla signed a free agent deal with the Mets that would ultimately lead to the team paying him $1.19 million every year through 2035, when he’ll be 72 years old.

After winning the NL East for the third straight year, the Pirates once again faced the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS. They fell behind in the series three-games-to-one. Their backs were against the wall and I was watching it all on TV, rooting for a miracle comeback. I was in college at the time and my baseball career had ended after one year, but I still followed the game avidly.

An added bit of drama was the upcoming departure of Barry Bonds to free agency when the season ended. Everyone knew the Pirates wouldn’t pay him what he deserved and he would head off to greener pastures (which he did, to San Francisco). Doug Drabek, who had won the NL Cy Young Award two years earlier, would also be a free agent (and would eventually sign with Houston). With those two stars soon to be out the door and the previous departures of Smiley and Bonilla, the core of those great Pirates teams would be gone. As a Pirates fan, I could feel that this was it; this was their last chance and it was dwindling away.

The Pirates battled back to win Game Five behind 35-year-old veteran Bob Walk and Game Six behind 25-year-old rookie knuckleballer Tim Wakefield. To give you an idea how different baseball was at the time, both Walk and Wakefield pitched complete games. Walk threw 128 pitches. Wakefield threw 141.

The series was now tied at three games apiece with Pirates ace Doug Drabek facing Braves ace John Smoltz. The winner of this game would go on to the World Series. This is the game MLB Network replayed on Friday—the game that broke my baseball heart.

It started well, with the Pirates taking a 1-0 lead in the top of the first inning on a sacrifice fly from Orlando Merced. They added a run on an RBI-single by Andy Van Slyke in the top of the sixth. Meanwhile, Drabek was tossing zeroes. He would take a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the ninth. The Pirates were three outs away from the World Series and I was watching on my TV at home, hanging on every pitch. I had a friend named Kevin who lived down the street. We could have watched the game together, but I didn’t want any distractions. He wasn’t a Pirates fan and I had to focus.

At this point, Drabek had thrown 120 pitches and was starting for the third time in the seven-game series. He had gone on three day’s rest in his previous start and was going on three day’s rest in this start. That’s what pitchers did back then. Smoltz was doing the same thing. In those days, the team’s ace was expected to pitch on three day’s rest in a seven-game series and it wasn’t unusual for a starting pitcher to throw well over 100 pitches.

The inning that broke me started with a double by Terry Pendleton. No big deal, right? It’s just one guy on base. Pittsburgh had a two-run cushion. ‘They’ve got this,’ I thought.

David Justice stepped up to the dish. The Pirates second baseman in 1992 was Jose Lind, who was a terrible hitter. He played 135 games that year and hit exactly zero home runs. He had a .275 on-base percentage and .269 slugging percentage. Both marks are brutal. He actually cost the teams nearly two wins (based on Baseball-Reference Wins Above Replacement).

The one thing Lind did best was field the ball (the second-best thing he could do was jump over Joe Garagiola). He won the Gold Glove that year thanks to his smooth hands and good range. In 745 chances, he’d made just six errors. If you could choose where David Justice would hit a ground ball, you would choose Jose Lind because there’s no way he would make an error in this situation. No way.

Justice hit a ground ball to second base, right where you’d want him to hit it. And Lind booted it. He just . . . he just booted it. Justice reached first and Pendleton went to third and I couldn’t believe it. Jose Lind didn’t make mistakes like that.

That brought up Sid Bream, a former member of the Pirates. He was the first baseman on their 1990 NLCS team, but left as a free agent that December. At this point, Bream was on the downside of his career. He was 31-years-old and had a bad right knee. He’d had five knee operations. You could even see the leg brace he was wearing underneath his uniform. He was a slow runner when healthy. With the leg brace, he ran like a man carrying a piano on his back. He was the perfect guy to have at the plate if you’re looking for a double-play ground ball, which is what the Pirates were hoping for.

Drabek walked him on four pitches. Drabek, who had very good control, who walked fewer than two batters per nine innings that year, who knew that Bream was the potential winning run, walked him on four pitches. That was the end of the night for Drabek, as Pirates manager Jim Leyland brought in shaky reliever Stan Belinda, who was their kinda-sorta closer. He definitely wasn’t a dominant closer like Dennis Eckersley or Lee Smith. In fact, he had just 18 saves all year, three fewer than someone named Joe Grahe of the Angels had that season.

The bases were loaded with nobody out, but the Pirates still led, 2-0. ‘They can still get out of this and make the World Series,’ I thought, as I watched from my couch on the other side of the country.

Ron Gant stepped to the plate to face Belinda. Gant was a muscular outfielder who hit more than 300 home runs in his career, including seven seasons with 25 or more. He was a threat, a big-time threat. Belinda, as has been mentioned, was a shaky closer. The fans in Atlanta, who had been quiet for a while, were up on their feet making noise. On the 1-0 pitch, Gant hit a ball deep to left field where Bonds caught it in front of the wall. I breathed a sigh of relief as Pendleton scored from third to make it 2-1. The Braves were a run closer, but the Pirates picked up an out and kept the tying run from going to third base. I was still confident.

The next batter to come to the plate was Damon Berryhill, a catcher who hit .228/.268/.384 that season, which made him about 20 percent below-average on offense. He was also a double-play candidate. This was a guy Belinda needed to go right after. Make him hit the ball. Heck, make him hit it to second base to give Jose Lind a chance to redeem himself.

Berryhill fouls off the first pitch. In the background, the Atlanta fans start their “tomahawk chop” gesture. The second pitch misses inside. The third pitch is similar to the second pitch, but closer to the plate. It looks like a strike to me, but Berryhill gets the call. That was a big pitch. Instead of 1-and-2, it’s 2-and-1. The fourth pitch is inside again for ball three, no question there. Pitch number five is beautiful, it’s right there . . . but the umpire calls ball four. He was wrong; that was a strike, and no one will ever convince me it wasn’t. Berryhill goes to first, Bream moves to second, Justice moves to third, and I move off the couch to the floor to change the Pirates’ luck because that’s what die-hard fans do.

The next batter for Atlanta was supposed to be Rafael Belliard, but they pinch hit Brian Hunter because Belliard is, literally, the worst hitter in baseball history since the live ball was introduced in 1920. (minimum: 2500 plate appearances). Belliard played in 1154 games in his career and hit two home runs. His career on base percentage was .270. His career slugging percentage was .259. It would have been managerial malpractice to let Belliard hit in that situation.

So it was Brian Hunter instead of Belliard at the plate with the bases loaded, one out, and the Pirates up by one. Shaky reliever Stan Belinda gets a strike on Hunter, then induces a pop out to second baseman Jose Lind for out number two. ‘Phushewwwww,’ I thought. ‘Just one more out to go and it’s World Series time, woot, woot.’

With the pitcher due up, the Braves go to their bench once again and select Francisco Cabrera to pinch-hit with their season on the line. Cabrera was mostly unknown. He had only appeared in 12 games all season long for the Braves, having spent much of the year in Triple-A. On the first pitch, shaky reliever Stan Belinda lives up to his name. He throws ball one. Announcer Sean McDonough says, “A most unlikely man in the spotlight for Atlanta, 25-year-old Francisco Cabrera.” Then Belinda throws ball two and I’m screaming at the TV, “C’mon, man! Throw a damn strike.”

On the 2-0 pitch, Belinda lays it over the heart of the plate and Cabrera crushes it to left . . . but it goes foul into the seats and I’m yelling, “Not there, damn it! Don’t pitch it there!”

McDonough says, “He had the green light on 2-and-0 and hammered it, but well foul over the Pirate bullpen.

Tim McCarver adds, unnecessarily, “And hit it very, very hard. Right in his wheelhouse and it hooks foul.” Yeah, we know, Tim.

Then came the worst moment of my career as a baseball fan. Shaky reliever Stan Belinda comes set, then throws the 2-1 pitch waist high on the outer part of the plate. Cabrera rips it into left field as McDonough shouts, “Line drive and a base hit! Justice to score the tying run, Bream to the plate…”

Bonds moves to his left to field the ball, then comes up firing. Sid “Knee Brace on His Leg, Piano on his Back” Bream is lumbering for home as Bonds lets the ball go. Catcher Mike LaValliere is standing to the first base side of the plate, trying to deke Bream into thinking there won’t be a play. The throw from Bonds tails up the first base line and LaValliere has to reach to his right to catch it, then dive back across the plate to tag Bream, but it’s too late and Bream scores. For a few seconds he just lays there on the ground looking into the sky before his teammates dogpile on top of him. I’m stunned.

As the Atlanta crowd cheers and the Atlanta players celebrate, the announcers stay quiet to let the scene play out. I’m staring at the TV, just demolished. It feels like two hours go by and the players are still celebrating and the fans are still cheering, but it’s only a couple minutes in reality. They show Bonds in left field, on one knee, left hand on his left hip, just watching. He gets up and starts to walk off, with the gold chain around his neck glistening in the Atlanta night. It would be the last play of his career as a Pittsburgh Pirate. They show more of the Braves celebrating and the crowd hasn’t let up at all and I hate every single person in the stadium.

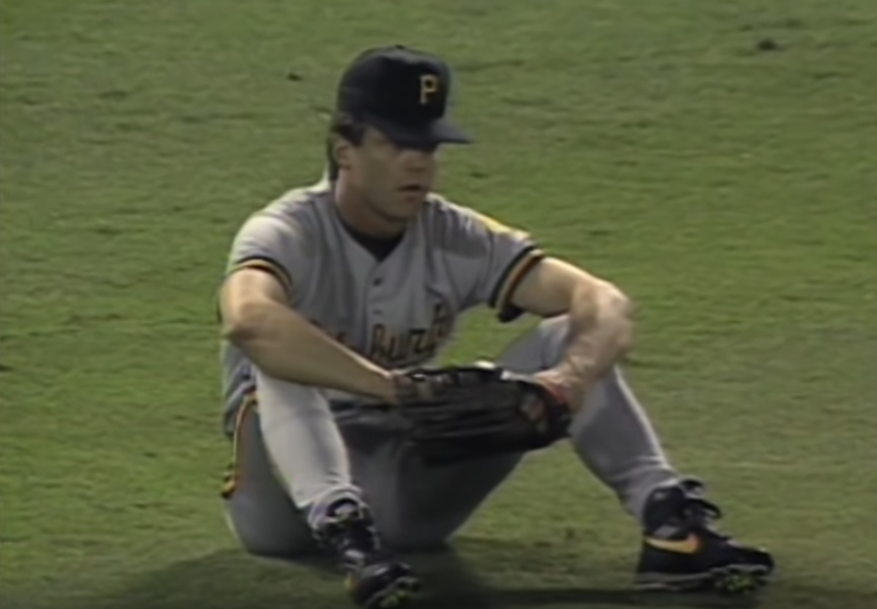

Then they show Andy Van Slyke in center field. This is the scene that has stayed with me for the last 28 years. Van Slyke is sitting on the grass, knees up, with his right hand in his glove and his cap tilted forward on his head and he’s staring in shock as the Braves players celebrate their come-from-behind-victory. I’ve never seen any player in a baseball game portray EXACTLY what I was feeling like Van Slyke did right then. Every Pittsburgh Pirate fan in the country was Andy Van Slyke at that moment.

Then the phone rings. It’s Kevin, someone I THOUGHT was my friend. I reluctantly answer the phone and all I hear is, “Hahahhahahahhahaha.” I tell him where he can go and I hang up the phone.

-Bobby Mueller