Frank Costanza Really Hated Under-appreciated Hitter Ken Phelps

Actor Jerry Stiller died recently. The 92-year-old was best known for playing Frank Costanza on Seinfeld, but his career goes back to the 1950s. One of his first gigs was working in Chicago with an improvisational company called The Compass Players, which later became The Second City. In the 1960s, Stiller was one half of the comedy duo Stiller and Meara, with his wife Anne being the Meara part of the duo. They appeared together on The Ed Sullivan Show throughout the 1960s, did five-minute sketch comedy on the radio in the 1970s, and had a short-lived TV sitcom in 1986.

In 1993, Stiller became Frank Costanza, on Seinfeld, the father of Jerry’s longtime friend, George. The part was originally written as a quiet, meek, milquetoast character who was constantly being screamed at by his wife, played by Estelle Harris, and it was played by a different actor.

When Stiller was first approached to be on the show, he rejected the part. He had never heard of Jerry Seinfeld or the TV show and was acting in a Broadway play. They called him again six months later, after the play was over, and he agreed to take the role. During the final dress rehearsal before the first episode he appeared in, he made the choice to perform the part in the loud, short-tempered, in-your-face way we all remember so well and it was an instant hit with everyone on the set. Those attributes came to define his character.

One of the interesting things about Seinfeld is that the co-creator of the show, stand-up comic Jerry Seinfeld, was probably the least funny person on the show. Neurotic George was hilarious, possibly the funniest person on the show. Kramer was a terrific physical comedian, bringing down the house just by walking in the door or with a look on his face. Elaine was aggressively funny, with laser-sharp wit. Newman was funny just standing there. David Puddy was dumb-funny. More than anything, it was all the people around Jerry Seinfeld who made the show as funny as it was.

Jerry Stiller, as Frank Costanza, was part of this group. After his recent death, The Ringer identified the best moments of Frank Costanza, which included his uneasy relationship with Jerry’s parents, his failed “serenity now” mantra to calm his temper, and his holiday creation, “a Festivus for the rest of us.”

The Ringer’s top Frank Costanza moment was when George Steinbrenner went to the Costanza’s home to tell Frank and Estelle that he feared their son was dead. In the midst of hearing this news, Frank yells at Steinbrenner, “What the hell did you trade Jay Buhner for?! He had 30 home runs, over 100 RBIs last year, he’s got a rocket for an arm, YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT THE HELL YOU’RE DOING!”

Steinbrenner responds with, “Buhner was a good prospect, no question about it, but my baseball people loved Ken Phelps’ bat. They kept saying Ken Phelps, Ken Phelps!”

This episode of Seinfeld originally aired on January 26, 1996. At the time, Buhner was coming off his first of three straight 40-HR seasons for the Seattle Mariners. The previous year, the Mariners had staged an epic comeback during the regular season to make the playoffs for the first time in their history. They went on to win the 5-game ALDS against the New York Yankees on Edgar Martinez’ epic double in the bottom half of the 11th inning, with Buhner collecting three hits in the deciding game.

Baseball fans watching that episode of Seinfeld were much more likely to have heard of Jay Buhner than Ken Phelps. In the 1995 post-season, Buhner had 11 hits in five games against the Yankees, then three homers in six games against Cleveland. Overall, he hit .383/.468/.702 in 51 post-season plate appearances. Yankees’ fans watching that episode probably remembered Buhner from the previous October.

Phelps, meanwhile, had been out of baseball for five years. He’d played much of his career in the distant outpost of Seattle, Washington. In the single biggest moment in his baseball career, he played the heel. On April 20, 1990, the Mariners’ Brian Holman had a perfect game going with two outs in the ninth inning. Phelps was sent to the plate to pinch-hit for Mike Gallego. On the first pitch he saw, he launched one over the right field fence to spoil Holman’s bid for perfection. That season, Phelps swung at the first pitch in roughly nine percent of his plate appearances (the league average was 14 percent) and this home runs was one of only two hits Phelps had when he swung at the first pitch.

There was a certain segment of fans knew who Ken Phelps was, even beyond his breaking up of Holman’s perfect game. Thanks to the many great Baseball Abstracts written in the 1980s by Bill James, who went from a baseball outsider who analyzed the sport during his down time as a security guard at a bean factory to a consultant for the Boston Red Sox franchise that won four World Series in 15 seasons, I knew Ken Phelps. When I saw this episode, I remember thinking, ‘Hey, Ken Phelps was really good!” I didn’t think Frank Costanza appreciated Phelps’ greatness. You probably don’t either.

In the 1987 Baseball Abstract, Bill James wrote an essay entitled “The Ken Phelps All-Star Team.” This is how it began:

See, on the one hand you’ve got the Henry Cottos, and on the other hand, you’ve got your Ken Phelpses. If Henry Cotto is a major league ballplayer, I’m an airplane. Cotto is one of those guys who runs well and throws pretty decent, and one year he hit .270-something (in less than 150 at-bats, in Wrigley Field, with a secondary average of .164), so you get guys like Don Zimmer who will rave about this great young prospect and keep trading for him, so he’ll get about eight chances to play in the major leagues before they figure out he can’t hit. At first when he doesn’t hit they’ll say he just needs more playing time, and then they’ll say he needs to stop wiggling his elbows while the pitcher is in motion, and then they’ll say he needs to point his lead foot and learn to keep his weight back, and then they’ll say he needs to be more aggressive at the plate, and then they’ll say he needs to go back to wiggling his elbows. They always figure that if you can run and throw they’ll teach you to hit. Of course they can’t teach anybody to hit, but they always think they can, so they keep trying.

Then on the other hand you’ve got your Ken Phelpses. Ken Phelps has been a major league ballplayer since at least 1980, when he hit .294 with 128 walks and a slugging percentage close to .600 at AAA Omaha, a tough park for a hitter. Through 1985 he had 567 at-bats in the major leagues—one season’s worth—with 40 home runs and 92 RBI. The Mariners still didn’t want to let him play. See, the problem was that Chuck Cottier, in his day, was a Henry Cotto, a guy who could run and throw, but couldn’t play baseball. Most major league managers were those kind of guys. Ken Phelps, on the other hand, can’t run particularly well (though he isn’t exceptionally slow, either) and doesn’t throw well, and if you’re that kind of player and want to play major league ball you’d better go 7-for-20 in your first week in the majors, or they’ll decide it’s time to take another look at Henry Cotto. Ken Phelps in his first two shots at major league pitching went 3-for-26. Despite his limitations, the man is a major league player. He’s a major league player because he plays good defense at first base and has a secondary average over .500, so that he can both drive in and score runs.

The biggest problem for Phelps is that he was good in a way that wasn’t appreciated in his day, which led to him spending way too many years in the minor leagues when he should have been playing in the big leagues. He had a terrific on-base percentage back when everyone cared way too much about batting average. He was often benched against left-handed pitching, so he was pigeonholed as a platoon bat. He was also limited to first base or DH. Despite his deficiencies, he was a good enough hitter that he deserved much more playing time than he received.

As an amateur, Phelps was talented enough to be drafted four times. He was first drafted out of Ingraham High School in Seattle in the 8th round of the 1972 June Amateur Draft by the Atlanta Braves. He didn’t sign with the Braves. Instead, he played one year at Washington State University under legendary coach Bobo Brayton.

Looking for an opportunity to play at Arizona State, Phelps transferred to Mesa Community College. After one season there, the Yankees drafted him in the 1st round of the 1974 January Draft. He didn’t sign with them either. The Philadelphia Phillies drafted him in the 1st round of the 1974 June Draft. Again, he didn’t sign. He still had his eyes on ASU, where he eventually played and was named to the College World Series All-Star team in 1976. The Kansas City Royals drafted him in the 15th round of the 1976 June Draft and he finally inked a professional contract.

Despite being drafted out of college, Phelps began his minor league career at the lowest level—Rookie League—and it took him five minor league seasons before he got a small taste of major league action. During one three-year stretch from 1978 to 1980, he walked 99, 98, and 128 times. Phelps was great at the most important thing a hitter can be great at—getting on base—yet he was mired in the minors. He finally received four plate appearances late in the 1980 season, when he was already 25 years old.

One of the problems for Phelps was the Royals’ talent at the major league level. During this time the DH spot belonged to Hal McRae, who was one of the best hitters on the team going back to the mid-1970s. When Phelps was crushing the ball in Triple-A in 1980 and 1981, McRae was the DH and Willie Mays Aikens was holding down the fort at first base for the Royals.

Before the 1982 season, Phelps was traded to the Montreal Expos for 39-year-old left-handed reliever Grant Jackson. He spent another year in Triple-A and it was by far his best season yet. He hit an incredible .333/.469/.706, with 46 home runs and 141 RBI. He was 27 years old and should have been doing this in the major leagues, but the Expos had sweet-swinging Al Oliver at first base (.331/.392/.514) and no DH spot because they were in the National League. Phelps just couldn’t catch a break.

Near the end of spring training in 1983, the Seattle Mariners purchased Phelps’ contract from the Montreal Expos. He was heading back to the American League, where he had two potential spots to play (1B or DH), rather than just one. It would be nice to have a time machine and go back to the 1983 season and force the Mariners to put Phelps in the lineup and just let him go. Instead, he played intermittently during April and May, a few games in June, and more at-bats in September.

Phelps once again spent significant time in the minor leagues, where he hit .341/.450/.759, with 24 homers and 82 RBI in 74 games. In 50 major league games, he hit .236/.301/.449. That may not seem like much, but it was 2 percent better than league average (102 wRC+; 100 is average). The Mariners’ primary first basemen that year—Gary Gray, Jim Maler, and Dave Revering—combined to hit .238/.298/.376, which was 19 percent below league average (81 wRC+). [Note: wRC+ is an offensive metric that adjusts for league and ballpark, where 100 is league average. It doesn’t take into account defense or the player’s position, just the bat. It’s a good number to use to compare players across teams, leagues, and time periods.]

On a bright note, Phelps played in 13 of the Mariners’ last 21 games and hit .300/.326/.575. At one point, he homered in three straight games. Perhaps the Mariners would give him a chance at regular playing time in 1984?

It turns out, they did. He started the 1984 season as the team’s regular first baseman and went 5-for-10, with 2 homers in his first three games. Unfortunately, he was hit by a pitch in his third game and suffered a broken hand, which sent him to the injured list. The Mariners brought up young Alvin Davis to play first base and the player who would become known as “Mr. Mariner” was named to the AL All-Star team and won the 1984 AL Rookie of the Year Award.

The broken hand was another stroke of bad luck for Phelps. With the emergence of Alvin Davis, Phelps was cut off from one of the two positions he could play. Still, he returned from his injury and ultimately played in 101 games with the M’s that year, hitting .241/.378/.521, with 24 homers. His 143 wRC+ was the best on the team (even better than Davis’ 140 wRC+). In fact, Phelps’ 143 wRC+ ranked 8th in the American League for hitters with 350 or more plate appearances.

Heading into the 1985 season, the Mariners had the reigning rookie of the year, Alvin Davis, at first base. He was seven years younger than the 30-year-old Phelps and much more likely to be a part of the team’s long-term future. They also had 34-year-old Gorman Thomas, a highly-paid trade acquisition before the 1984 season who had suffered a season-ending rotator cuff injury in June. He was now healthy and slated to be the full-time DH in 1985, which meant Phelps was the odd man out, despite essentially being the best hitter on the team the previous season.

After having 360 very productive plate appearances in 1984, Phelps was limited to 140 plate appearances in 1985 and hit .207/.343/.466. The .207 batting average looks terrible, but the .343 on-base percentage and .466 slugging percentage were both above league average. His 119 wRC+ was worse than Alvin Davis (125 wRC+), but better than Gorman Thomas (111 wRC+). Still, Thomas received much more playing time and led the Mariners with 32 homers.

All three hitters were back with the M’s in 1986, so the playing-time crunch continued for Phelps in the first half of the season. Thomas started off the year fine, but began to struggle in May and June. By June 24, he was hitting just .194/.308/.394 in 199 plate appearances. Meanwhile, Phelps was crushing the ball–.265/.423/.657.

After being in the dark for so long, the Mariners finally saw the light. They released “Gormbo” on June 25 and gave Phelps a chance. He finished the season with a team-leading 148 wRC+ in 441 plate appearances, which was the most plate appearances he would have in a single season in his career. Among all American League hitters with 400 or more plate appearances in 1986, only Don Mattingly and Wade Boggs had a higher wRC+ than Phelps. Unbeknownst to most everyone, Phelps was one of the best hitters in the league.

It was more of the same in 1987. Phelps hit .259/.410/.548, good for a 148 wRC+, which once again led the Mariners. This time he finished 7th in the AL in wRC+, behind Wade Boggs, Paul Molitor, Mark McGwire, Dwight Evans, Alan Trammell, and Rickey Henderson (among players with 400 or more plate appearances). Four of those six players are now in the Hall of Fame and the other two have solid cases for Cooperstown.

This brings us to the fateful year, 1988. This is the year Phelps was traded to the Yankees for Jay Buhner. Eight years later, Frank Costanza would have his signature moment on Seinfeld when he had the opportunity to do what so many Yankees fans dreamed about—yell at George Steinbrenner for a bad trade.

It’s true that this was a bad trade, but not because of anything Phelps did. After being traded to the Yankees, he hit .224/.339/.551 in 127 plate appearances (141 wRC+), which was better than Buhner hit for the Mariners that year (.224/.320/.458, 113 wRC+). The problem was, Phelps wasn’t going to play first base ahead of Don Mattingly and he wasn’t going to get much time at DH behind Jack Clark. He had a better wRC+ than both, but they were the incumbent starters with bigger contracts.

Also, Phelps was 33 years old, while Buhner was 23. Phelps would play just two more seasons, while Buhner would play 13 more. It was a bad trade for the Yankees because they traded a young, cost-controlled outfielder for an aging veteran and didn’t have a spot for that veteran to play regularly. Frank Costanza was right, but his famous TV criticism may have tainted the good name and slighted the productive career of Ken Phelps.

Twenty-seven years after the trade made famous by Seinfeld, Jay Buhner and Ken Phelps were in the announcer’s booth together during a spring training game in 2015. In the clip, they are asked about the trade that made them famous. Buhner talks about being excited to get a chance to play every day with the Mariners and also mentions how remote Washington state was to a guy playing in New York:

Buhner: “I was a little apprehensive, though, at first. Uhh, ‘cause let’s face it, I didn’t know if there was, you know, Washington state, everybody thinks Washington D.C., Washington state, they still get mixed up.”

Then they ask Ken Phelps about the deal and he said: “Well, I told Bone when I got traded at the time, you know, you went on to have one heckuva career, no doubt about it, but I try to tell people I was a little better than you before you went off to, and got off on it, but he may never admit it. But I was established at the time. And I was, you know, he was gonna be, shortly thereafter, so that’s my excuse and I’m stickin’ to it.”

Phelps closed the conversation with: “That was fun times. You know, it’s great to be remembered for something, isn’t it, Bone? You know, whether it’s good or bad. There’s no bad press. There really isn’t any bad press. It’s just good to have guys remember who you are.”

There’s no question that Jay Buhner had more career value than Ken Phelps. Buhner had 22.3 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) to Phelps’ 9.5 (per FanGraphs). Of course, Buhner also had about 3700 more plate appearances and WAR is a cumulative stat. The more you play, the more you can accumulate WAR. If you pro-rate Ken Phelps WAR/Plate Appearance (PA) to a 600-PA season, he would be a 2.5-WAR player, which is slightly better than Buhner’s pro-rated WAR of 2.3.

When you look just at their hitting production, Phelps finished his career with a 131 wRC+, meaning he was 31 percent better than average when league and ballpark are taken into account. For all hitters with 2000 or more plate appearances since 1980, Phelps ranks 64th out of 1179. He’s between Ken Griffey, Jr. and Jose Canseco. Buhner has a 123 career wRC+, which places him 118th of 1179 players since 1980. He’s between Robin Yount and Jorge Posada.

Not only was Phelps a better hitter than Buhner for their entire careers, he was significantly better when both were at their peak. During his five-year peak from 1984 to 1988, Phelps had a 147 wRC+, which ranked 5th in baseball for players with 1500 or more plate appearances during that time. You’ve heard of the four players ahead of him: Wade Boggs, Jack Clark, Pedro Guerrero, and Darryl Strawberry. Right behind him were Don Mattingly and Will Clark. That’s the kind of hitter Ken Phelps was when he was at his very best. In contrast, during his five-year peak (1993-1997), Buhner had a 130 wRC+, featuring Ryan Klesko and Matt Williams as contemporaries with similar productivity.

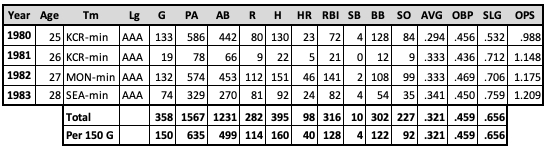

This doesn’t even take into account how well Phelps hit in Triple-A. As Bill James said in the above quote, Phelps should have been in the major leagues in 1980. Consider how he hit in 358 Triple-A games from 1980 to 1983 (which included the strike-shortened 1981 season):

How is that guy NOT playing regularly in the show? Phelps unfortunately, spent most of his peak years one level below the big leagues.

Jerry Stiller, as Frank Costanza, was right about the Buhner-Phelps trade. It was a bad one for the Yankees, but it was the specific circumstances of the deal, not the caliber of the players. Phelps was much better than most people realize.

Two years after his Buhner-Phelps tirade, Frank Costanza had another chance to yell at Steinbrenner in “The Finale, Part 2.” Once again, he told it like it was when he yelled, “How could you give 12 million dollars to Hideki Irabu?!” You tell him, Frank! (RIP Jerry Stiller)

-Bobby Mueller