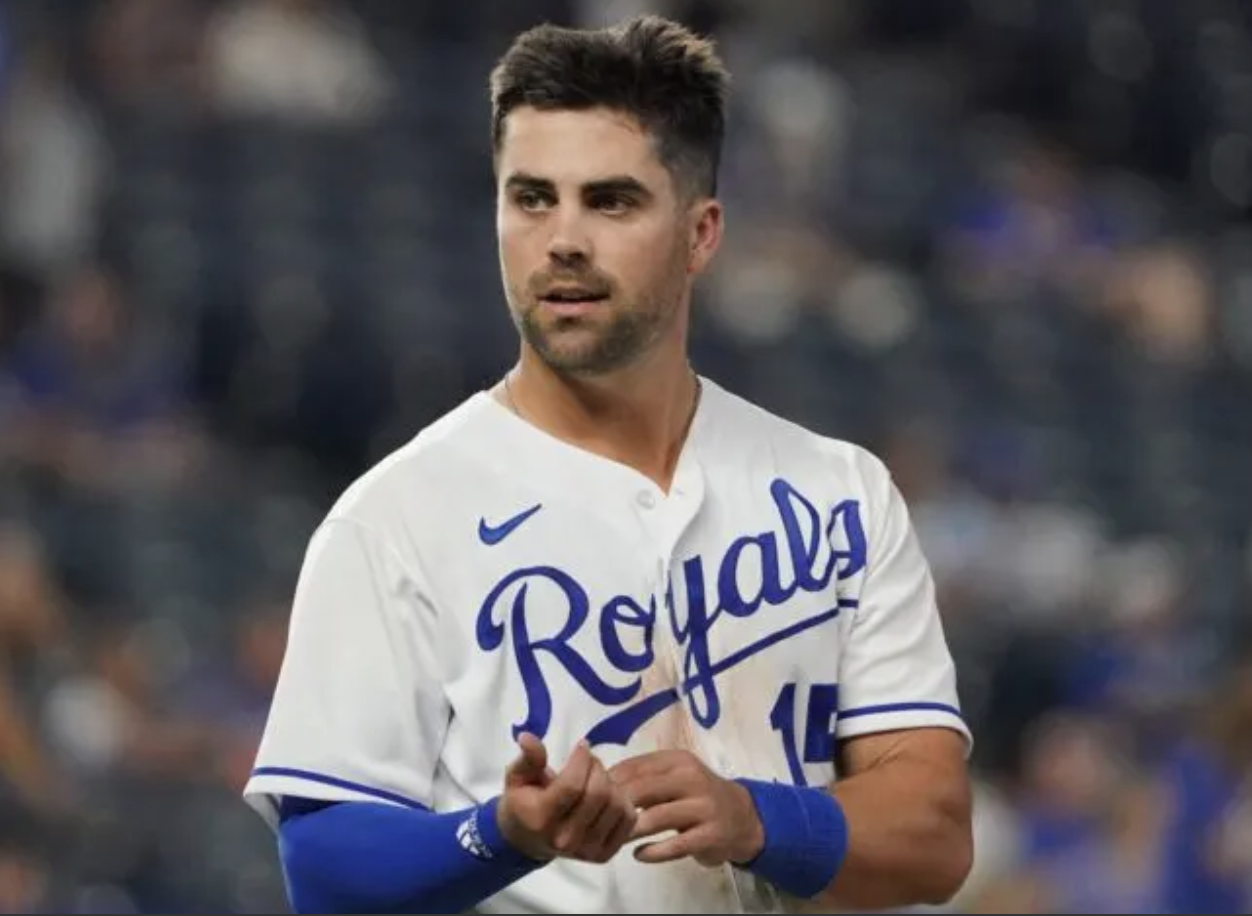

What’s Wrong With Whit Merrifield?

Entering action on May 2nd, the Royals’ Whit Merrifield held a triple slash line of .159/.213/.195 with an OPS+ of 21. For some perspective, among the 122 players with a minimum of 80 PA, Merrifield ranks 114th, 119th, 121st, and 120th in each of those respective categories. All of that includes the two hits he had in four at bats on Sunday afternoon to give the numbers a little bit of a boost.

As you’re a reader of Off the Bench Baseball, I likely don’t need to remind you that Merrifield is a two time All-Star, and although his value has been in part due to being a plus defender at multiple positions and a plus baserunner, he’s been a better than average hitter too. From 2017 through 2022 Merrifield led MLB in hits twice, doubles once, and triples once while posting a 107 OPS+ over 3,057 PA. Again, for a player who’s played every position besides catcher and shortstop, that’s pretty good.

So what’s wrong with Whit Merrifield?

Taking a closer look at the numbers, we don’t learn too much. Merrifield has always been an aggressive, high contact hitter, with good speed but not too much power (although his .439 SLG from 2017 through ’21 tops the league average of .428 over that span). So far in 2022 he’s maintained the same level of aggression as always, as his first pitch swing percentage, overall swing percentage and walk rate are all within one percent of his career norms. Meanwhile his chase rate is almost two points lower than his career norm, so we can’t accuse him of being overly aggressive either.

As far as the high contact aspect, although his contact rate of 77.1 percent is 5.4 percentage points below his career norm, it’s still better than league average and not nearly enough of a discrepancy to explain the massive drop-off in production. Somewhat interestingly, his previous single season low contact rate came in 2019 when he led the league in hits and triples while posting the second best OPS+ of his career. Additionally, his current strikeout rate of 13.5 percent puts him on the top ten percent of baseball, just as it was the two seasons prior to that. Simply, his rate of contact is not a problem.

When we look more closely at what type of contact Merrifield is making, we don’t get too much help there either. His current 2022 average exit velocity of 86.7 mph is essentially the same as his career norm of 87.1 mph, while his current launch angle is less than one degree from his career average as well. Even his xBA of .260 is only slightly below his career .274 xBA, and is still better than the MLB average.

Looking at “where’ the batted balls have been going is only slightly more interesting as the percentage of balls Merrifield has pulled is up 5.7 percent over his career average, while his opposite field batted balls have dropped by five percent. Although those aren’t insignificant changes, they’re not eyebrow raising by any means and are more likely the result of a small sample than anything else. (That explanation seems more likely than a 33 year old hitter with a good track record making a philosophical change of that nature in the batter’s box.)

Speaking of Whit’s age, his sprint speed currently ranks in the 89th percentile across MLB while his outfielder burst comes in at the 87th percentile. Not that reduced speed would explain the big reduction in in results, but we can safely rule that out as any factor at all. Additionally, he’s been very rarely shifted against in 2022 as has always been the case throughout his career. That is to say, defenses haven’t made noticeable adjustments to his batted ball profile.

There are some numbers however, that are quite different thus far in 2022 when compared to previous performances in Merrifield’s career. As we already noted, his current xBA is .260, but his actual batting average is .159. If an over 100 point discrepancy between an expected outcome and reality didn’t grab your attention, perhaps this will: Despite only very small changes in his batted ball profile, Merrifield currently possesses a .183 BABIP. Not only is that lower than all but five MLB players with at least 80 PA this season, but it’s 143 points lower than his career BABIP average of .326, and .112 lower than his previous career low of .295 ( and even that can be considered an outlier as it occurred in the shortened 2020 campaign.)

If you want to say that Merrifield is simply regressing as a player, I wouldn’t dismiss that outright – after all, his 2021 season as a hitter wasn’t great. However, I would respectfully argue that you’d be vastly underestimating the impact of randomness and luck on player performance if you took that stance. When comparing his current BABIP to his career standards, and his xBA to his actual batting average, it’s hard to conclude that there’s a factor in his lack of production so far this season that’s bigger than simple bad luck. Given that we’re dealing with a small sample size*, I’m of the mind that the answer to our earlier question, “What’s wrong with Whit?” is “Nothing is wrong with Whit.”

(*Yes, even a month is a small sample size. Players who hit .300 on a season don’t get 30 hits every 100 at bats, as much as we fans often seem to think that’s the case.)

Furthermore, I think this may also shine a light on the perceptions we fans have of certain types of players. It’s a common assumption that power hitters that are more “all or nothing” are streakier than players who put the ball in play consistently. We often say of power hitters that their home runs “come in bunches” but they’re also prone to extended slumps. (As a fan of the Yankees, I can tell you I’ve heard that characterization of Giancarlo Stanton and Joey Gallo enough to last me a lifetime.)

Yet what Merrifield is showing us, in large part due to randomness and small sample sizes, is that contact hitters are just as prone to slumps as power hitters. It just doesn’t seem that way because they make contact and something happens (as opposed to some cringe worthy strikeouts we see from power hitters sometimes.) Especially in today’s game where defenders cover more ground and have stronger arms than ever, if you don’t consistently hit the ball very hard and elevate it, you’re susceptible to stretches of everything of moderate exit velocity and on the ground becoming an out. It may not look as bad as a high number of strikeouts, but Joey Gallo’s horrid start of .180/.275/.295 and 70 OPS+ is far better than Merrifield’s, even with Gallo’s 42 percent strikeout rate.

The good news for Merrifield is that fortune has a tendency to even out, both for contact hitters and for those who swing for the upper deck. Results based statistics will always be at the mercy of small sample sizes – after all, Bryce Harper was hitting .332 with a .598 slugging after 33 games last season – but only had 10 RBI. If you’re a fan of Merrifield, or any similar hitter who’s struggling, just remember that .300 hitters don’t get 30 hits every 100 AB, just like run producers don’t drive in four per week for 25 weeks to reach 100 RBI.