Let’s Add 19 Catchers to the Hall of Fame

Have you ever taken a guided tour of a cave? The backstory is always something like, “In 1821, Farmer Wilson was tending his cattle when a crack opened in the ground and swallowed his favorite Heffer.” Or maybe like, “Three teenagers were playing with some spare TNT they looted from an army base in 1923 and discovered a massive cavern system.” These natural wonders took millions of years to form and were right under our feet the whole time, but we were none the wiser.

That’s analogous to our knowledge of catcher value. For the entire history of baseball until about a dozen years ago, we kind of assumed catcher defense was important in a special way, but we had no way to measure it other than caught-stealing percentage. We had no idea just how massively important it was until we learned to quantify pitch framing.

The problem is that, in our exploration of this newfound cavern, we immediately hit a fork in the tunnel. We turned in one way, which led to a much more advanced understanding of present and future catchers, but we never doubled back to explore the other prong — reevaluating catchers of the past. If decrepit, old José Molina suddenly became super valuable to the 2012-2014 Rays despite having no other skills than pitch framing, what does that say about Jim Sundberg‘s entire career?

The catcher position has always been far more important than we’ve given it credit for. In spite of this, there are only 19 catchers in the Hall of Fame! The only position with fewer Hall of Famers is third base (17). Given how grossly we’ve underestimated backstops all these years, the Hall voters need to reframe their collective decision-making regarding the position.

Given that it was already an underrepresented position group before even considering framing and defense retrospectively, we should double the number of catchers in the Hall to 38. Here are the next 19 who deserve a plaque.

Borderline Candidates

Any catchers on the fence immediately get welcomed over.

Bill Freehan– Defense factors heavily into this exercise because that’s the main reason why catchers were overlooked. Freehan was an 11-time All-Star who won five Gold Gloves in 15 years for the Tigers. He earned consecutive top-three MVP finishes in 1967 and 1968.

Thurman Munson– Even under the traditional framework for Hall-of-Fame catchers, Munson belongs in Cooperstown. The 1976 AL MVP is 12th in JAWS, which is the highest of any catcher not currently in the Hall except for Joe Mauer, who isn’t eligible yet. His WAR7 trails only Gary Carter, Johnny Bench, Mike Piazza, Iván Rodríguez, Mauer, Yogi Berra, and Carlton Fisk.

Jorge Posada– It’s a little harder to argue for Posada because his defense was actually subpar. Still, he posted better era-adjusted numbers in his 17-year career than Hall of Famers Ernie Lombardi, Ray Schalk, and Rick Ferrell. (Even by doubling the position group, Ferrell probably doesn’t deserve to be enshrined. However, this is about putting more players in, not taking them out.)

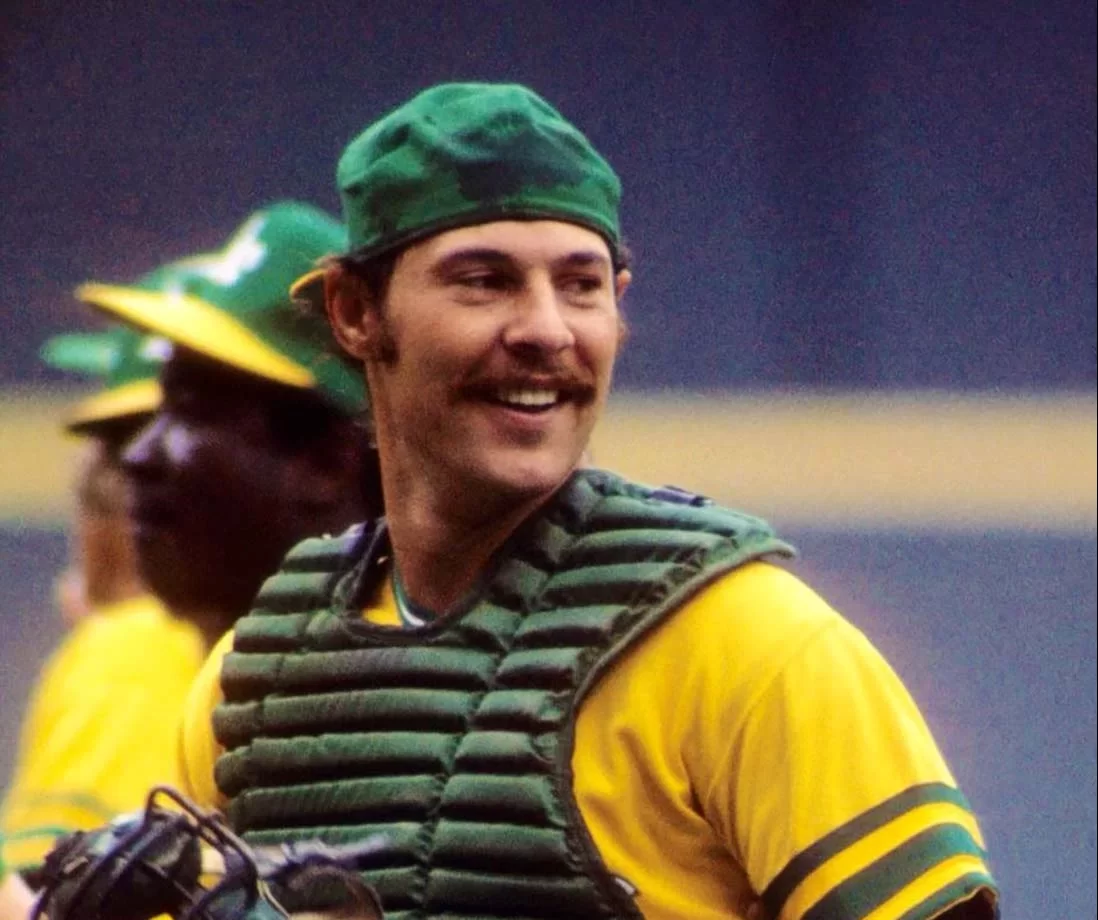

Gene Tenace– In the 1970s, people underappreciated Tenace twice over. They failed to recognize his value as a catcher as well as his stellar .388 career on-base percentage. He led the league in walks twice and won four World Series championships — including the 1972 World Series MVP award.

Negro Leagues, Cuban Leagues, and Black Baseball

There are four current Hall-of-Fame catchers from Negro League baseball: Roy Campanella, Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, and Luis Santop. Despite recent inductions, the Hall still does not have equal representation of players from the Negro Leagues, Cuba, and other Black baseball leagues. (Hat tip to Seamheads and Hall of Stats for help compiling these names, as well as the SABR Bio Project.)

Frank Duncan– Duncan was best described by his Kansas City Monarchs teammate, pitcher William Bell. “Dunk was an excellent catcher. Every owner wanted him. He played in nearly as many places as Hamlet: The Philippines, Japan, Hawaii, Cuba, South America, and North America.” He enjoyed a 22-year playing career followed by a successful stint as manager of the Monarchs from 1942-1947. From 1926-1930, he slashed .323/.408/.453.

Regino García- García was among the premier catchers in the early Cuban leagues from 1901-1914. He was elected to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1941.

Gervasio González- González was part of the initial induction class of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. He played from 1901-1919, primarily for Almendares.

Mitchell Murray– Murray was one of the top hitters of the 1920s. From 1922-1926, playing mostly for the St. Louis Stars, he hit .388 with a 139 OPS+.

Quincy Trouppe– Trouppe was truly one of the great ambassadors of baseball. His playing career began with the St. Louis Stars as a 17-year-old switch-hitting catcher in 1930 and culminated with the Cleveland Indians in 1952. Along the way, he donned a myriad of uniforms, with his most productive years occurring from 1939-1944 in the Mexican League. He was a successful player/manager for the Cleveland Buckeyes and Chicago American Giants, then later became the first African American scout for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Doc Wiley– Wiley was among the best players on the legendary barnstorming New York Lincoln Giants in the 1910s. In games for which we have box scores, his batting average was at least .314 in every season from 1913-1918.

Not Yet Eligible

Players must be retired for five years before Hall consideration.

Joe Mauer- In his 15-year career with the Twins, Mauer won three batting titles, three Gold Gloves, and the 2009 AL MVP. He is seventh all-time in catcher JAWS ahead of Hall of Famers Bill Dickey, Gabby Hartnett, Mickey Cochrane, and Ted Simmons.

Yadier Molina– If we’re properly considering catcher defense, Molina is a no-doubt Hall of Famer. His nine Gold Gloves (and counting?) are the third most ever by a catcher trailing only Iván Rodríguez (12) and Johnny Bench (10). Of course, to get to the Hall he will have to eventually retire someday.

Buster Posey– Posey retired this past offseason following one of his best years, albeit for good reason. In a relatively short career, he won the 2010 NL Rookie of the Year, 2012 NL MVP, and three World Series rings. Altogether, his resume is very similar to Thurman Munson’s.

Old-Timey Greats

Ironically, catcher was viewed as a defense-first position more than 100 years ago and any offense was a bonus. Now we’ve come full circle.

Charlie Bennett– Bennett first personified the term “everyday catcher” at a time when mitts weren’t padded yet. He obliterated early National League records for games caught in a season and career. During his peak for the Detroit Wolverines from 1881-1888, he compiled a 143 OPS+.

Wally Schang– Schang was a switch-hitter who straddled two distinctly different eras of baseball, playing from 1913-1931. He played for four different dynasties: the Philadelphia Athletics of the early 1910s, the Babe Ruth-as-a-pitcher Red Sox, the Babe Ruth-as-a-slugger Yankees, and the second great Athletics group in 1930. His .393 career on-base percentage is fifth-best by a catcher in MLB history (minimum 1,000 PA).

Charles Zimmer– Zimmer was among the most respected game-callers of the 1800s, playing from 1884-1903. He spent most of his career with the Cleveland Spiders where Cy Young himself credited Zimmer for developing him as a young pitcher. In 1900 and 1901, he was the leader of an early players union and successfully negotiated to repeal the reserve clause (though the AL and NL later ripped up the agreement). He then became a manager and umpire.

Defense

If there are defense-first middle infielders in the Hall, such as Ozzie Smith, Rabbit Maranville, and Bill Mazeroski, there should be a few catchers in for the same reason.

Bob Boone– Boone would’ve won more than seven Gold Gloves if so much of his career hadn’t overlapped with Johnny Bench’s. He collected his last Gold Glove in 1989 at age 41; only Greg Maddux won one at a more advanced age. Using dWAR for catchers is imprecise at best, but his 25.8 career dWAR is fourth-best ever behind Iván Rodríguez, Yadier Molina, and Gary Carter.

Jim Sundberg- Sundberg’s 25.3 dWAR is right behind Boone’s and his overall JAWS is similar to Molina’s and Charlie Bennett’s. He averaged 4.1 WAR per season from 1977-1982 and owns six Gold Gloves.

In His Own Category

Elston Howard– Howard didn’t get to play his natural position on a regular basis until 1960 when he was already 31 years old. He debuted with the Kansas City Monarchs as a teenager in 1948, then had his contract purchased by the Yankees in 1950. He served in the military in 1951 and 1952 before resuming his career in the minor leagues. When he was called up to New York in 1955, he was blocked at catcher by Yogi Berra. In spite of all of the roadblocks, he became a 12-time All-Star and won the 1963 AL MVP at age 34. If he had the chance to play as a catcher in MLB from the onset of his career, there’s no doubt he would be in the Hall of Fame today.

One More?

If you’ve been counting along, we’ve now added 18 catchers to the Hall, leaving us one short of the goal. At this point, there is a bit of a dropoff in quality. Depending on your big-Hall/small-Hall preference, you could approve of any number of the following players for enshrinement — or possibly none at all! At the risk of crossing into the absurd…

Borderline Candidates- Jason Kendall and Russell Martin

Negro Leagues- Tommie Dukes and Tom Young

Not Yet Eligible- Salvador Perez and J.T. Realmuto

Old-Timey Great- Johnny Kling

In His Own Category- Joe Torre, who is already a Hall of Famer as a manager. No one has ever been inducted as both a player and in another capacity.