Miguel Cabrera: Detroit Tigers’ slugger going out with a whimper, not a bang

Miguel Cabrera has been a delight to watch play baseball over the last 21 years simply because he expresses so much joy playing baseball. He‘s had mischievous interactions with his teammates, opposing players, umpires, and fans, especially when chasing foul balls that went into the stands. He often had a big smile on his face. One of his favorite on-field foils was the diminutive Jose Altuve and he was particularly fond of touching the head of Adrian Beltre, something Beltre famously hated. With the elimination of the four-pitch intentional walk, Cabrera’s intentional walk hit in 2006 is the last one longtime baseball fans will remember.

Now Cabrera is winding down a Hall of Fame career. With more than 3,000 career hits, 500 home runs, 1800 RBI, and a .307/.382/.519 batting line, he’ll undoubtedly be inducted into the Hall of Fame on his first ballot, joining a select group of six players currently in the 3,000 hit/500 home run club. The others are Henry Aaron, Albert Pujols, Álex Rodríguez, Willie Mays, Rafael Palmeiro, and Eddie Murray.

Cabrera was signed by the Marlins out of Venezuela as a teenager. He made it to the big leagues in his fourth professional season, along the way playing in the minor leagues with Adrián González and Dontrelle Willis, both of whom have been retired for quite some time now. One of his teammates in his rookie year back in 2003 was 38-year-old Lenny Harris, who had previously played for Pete Rose as a member of the Cincinnati Reds in 1988.

In Cabrera’s rookie year, Andre Agassi was the #1 player in men’s tennis, Annika Sörenstam became the first woman to play the PGA Tour in 58 years, and Barry Bonds became the first player in MLB history to have 500 career homers and 500 career steals. Sheryl Crow and Eminem won American Music Awards, “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” debuted on TV, and rapper 50 Cent won the Billboard Album of the Year. This was years before he threw one of the worst first pitches of all time at a Mets game. Miguel Cabrera has been playing so long, he was a rookie the year MySpace launched, back when the creators of social media networks just wanted to be your friend and didn’t desire global world domination.

From his rookie season through his early 30s, Cabrera was Mr. Reliable. He made the All-Star team 11 times in 13 years, won seven Silver Slugger Awards, led the league in batting average and on-base percentage four times, slugging percentage two times, and has two MVP Awards. The first of his back-to-back MVP seasons came in 2012, when he won MLB’s first Triple Crown since Carl Yastrzemski in 1967. His Marlins won the World Series in his rookie year, surprising the Yankees in the six-game series. He made it back to the postseason in four straight seasons from 2011 to 2014 with the Detroit Tigers, but lost in the World Series once, the ALCS twice, and the ALDS once.

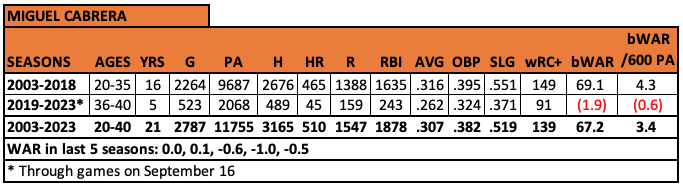

In the end, age comes for us all and Miguel Cabrera is not immune to the eroding winds of time. After being one of the greatest hitters of his generation for 16 years, Cabrera’s production dropped precipitously in 2019 at the age of 36. The chart below shows the stark difference between Cabrera at his best and what came after.

For reference, a 149 wRC+ means Cabrera was 49 percent better than average on offense when league and park effects are taken into account (a 100 wRC+ is exactly league average). His 149 wRC+ through his age 35 season is in the range of the career marks of Mike Schmidt, Jeff Bagwell, and Edgar Martinez. That’s the caliber of hitter Miguel Cabrera was during his first 16 seasons. In his last seven seasons, he’s been nine percent below average as a hitter. His current 139 wRC+ puts his career offense in the range of such hitters as Duke Snider, Reggie Jackson, and Norm Cash. Those are still great hitters, but not at the level of Schmidt, Bagwell, and Martinez.

Cabrera was worth 4.3 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) per 600 plate appearances (PA) in his first 16 years (using Baseball-Reference WAR). Typically, players worth 4-5 WAR are All-Stars, which Cabrera regularly was during this time. This is when he built his case for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

From age 36 on, he’s been below replacement level. Hypothetically, Cabrera could have retired after his age 35 season with a Hall of Fame resume that included nearly 70 WAR and that impressive 149 wRC+, but “only” 2676 hits and 465 home runs. Instead, he played another five years as a below average hitter providing sub-replacement-level production, but pushed his hits and home run totals into the elite 3,000-hit/500-HR club.

Is this what we want from legendary players? Continuing to play as below-average players, but eclipsing impressive milestones along the way? This isn’t as rare as you might think. There have been other Hall of Fame caliber players who limped to the finish line of their careers.

Pete Rose

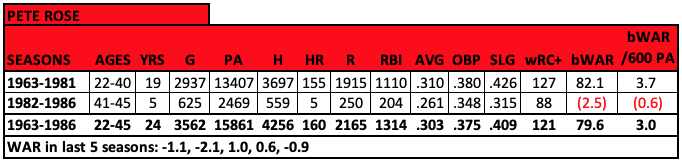

“Charlie Hustle” is not in the Hall of Fame because he gambled on baseball, but he had a Hall of Fame career as a player. He played in more games, had more plate appearances, and more hits than any other player in MLB history. While that is certainly impressive, like Miguel Cabrera, Pete Rose also had a significant drop-off in production at the end of his career but remained a regular in the lineup to add to his counting stats.

Rose was consistently an above average player through his age 40 season, a span of 19 years that began with his rookie year in 1963 and lasted through the 1981 season, when he was worth 1.7 WAR while playing in 107 games during the strike-shortened season. He was not known as a power hitter, but for much of his career he would bang out 35-45 doubles a year, 5-10 triples, and had eight seasons with between 10 and 16 homers.

In 1982, Pete Rose played 162 games, had 718 plate appearances, and hit three home runs. Three. A first baseman could never get away with that in 2023. He slugged .338. This inability to hit for power would continue for the rest of his career. After slugging .426 over his first 19 years, he slugged .315 in his final five. He went from averaging 3.7 WAR/600 PA to being below replacement level over his last five seasons, much like Cabrera.

After the 1981 season, Rose had 3697 hits, which ranked third all-time. Hank Aaron was just 74 hits away. Rose passed Aaron in 1982 when he had 172 hits, but his .271/.345/.338 hitting line was below average (92 wRC+) and he was a below replacement-level player (-1.1 WAR) because of his less-than-stellar defense and baserunning.

He was even worse as a member of the 1983 Phillies “Wheeze Kids” team that included the 42-year-old Rose, 41-year-old Tony Perez, 39-year-old Joe Morgan, 38-year-old Steve Carlton, 38-year-old Tug McGraw, and 40-year-old Ron Reed. That team famously made it to the World Series, which they lost in five games to the Baltimore Orioles. Rose was the face of the team, but it was by far his worst season in the big leagues as he hit just .245/.316/.286 (68 wRC+) and was well below replacement-level (-2.1 WAR).

By this point, Rose had passed Aaron for second place all-time in career hits. He stood at 3990 and was desperate to pass Ty Cobb’s record, which was thought to be 4191 at the time but has since been revised to 4189. Rose signed as a free agent with the Montreal Expos and collected his 4000th career hit in mid-April. After hitting .259/.334/.295 (83 wRC+) for the Expos in his first 95 games, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds and immediately named player-manager. Now he could write himself into the lineup whenever he wanted.

To his credit, Rose finished out the 1984 season in Cincinnati on a heater, with a .365/.430/.458 batting line in his final 26 games. With the luxury of having himself as the manager, he broke the hits record in 1984, then added to it in 1985, when he hit a truly awful .219/.316/.270 (66 wRC+) as a 45-year-old. He achieved his goal of passing Ty Cobb on the all-time hits list, but it wasn’t pretty.

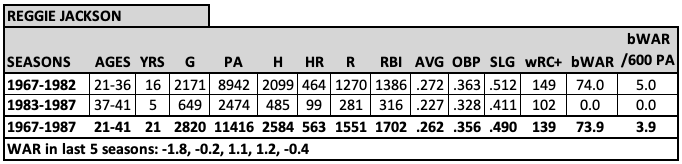

Reggie Jackson

Jackson had his last great season in his first year with the California Angels in 1982 after five tumultuous seasons with the Yankees. He led the AL with 39 homers (and 156 strikeouts), was an All-Star, and finished sixth in AL MVP voting. He was worth 3.1 WAR. It all came crashing down in 1983, though, when he hit just .194/.290/.340 and was limited to 116 games. That was the first (and the worst) of three below-replacement-level-player seasons in his last five years despite hitting another 99 home runs during this time.

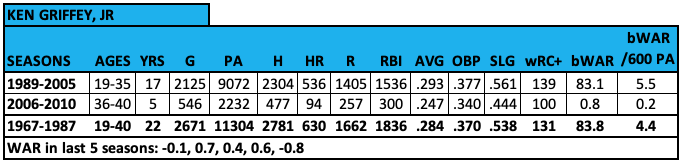

Ken Griffey Jr.

After requesting to be traded away from the Seattle Mariners after the 1999 season, Ken Griffey Jr. never came close to the heights he’d reached in the Emerald City. He was a great player in his first year in Cincinnati, when he hit 40 homers, had a 127 wRC+, and was still good on defense. He was worth 5.5 WAR that year (he had seven seasons with more WAR as a Mariner). Over the remaining nine years of his career, he would be an above average player over a full season just one time (above average = greater than 2 WAR).

Griffey’s last five years included 94 homers and a league average 100 wRC+, so he wasn’t awful with the bat, but his defensive ability had eroded so drastically due to ongoing health problems that he was barely above replacement-level while continuing to play the outfield with the Reds into his age-38 season. There was no DH in the National League then.

He finished out his career with a half-season with the White Sox and two final seasons back in Seattle, although everyone probably would have been happier had he not come back in 2010 when he hit .184/.250/.204 (31 wRC+) and suddenly left the team mid-season without telling his teammates, manager, or general manager beforehand.

Ted Simmons

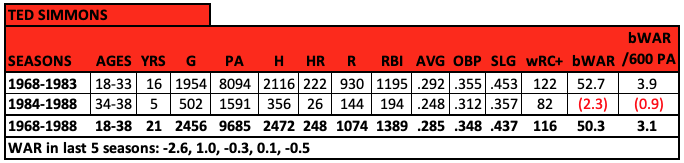

In writing this piece, I’m struck by how quickly some all-time great players went from being highly productive one season to quite awful the next. For Simmons, the downfall came in 1984 at the relatively young age of 34. The previous year, Simmons had been an All-Star and earned down-ballot AL MVP votes while starting 83 games at catcher and 66 at DH. Over the remaining five years of his career, his time behind the plate was significantly reduced as he slotted in most of his time at DH for the Brewers in 1984 and 1985, then finished out his career as a first base/third base utility player for the 1986 to 1988 Atlanta team, hitting just .248/.323/.367 (79 wRC+) in his final three seasons.