If you believe in reports from the start of the 2016 season, the strike-zone for the MLB could be shrinking next season. It seems every so often, particularly since the start of the decade, efforts are made to increase offense. The powers that be have messed with the strike zones and floated the idea of the DH coming to the National League (no, just no). What can be overshadowed by these somewhat pedantic debates is that baseball, and in particular the aforementioned NL, currently is experiencing a Golden Age of pitchers. Amongst all the eye-popping statistics and spectacular performances so far, one name seems to be at the fore-front of almost every Cy Young debate: Clayton Edward Kershaw.

Clayton Kershaw is almost unbelievably trailing Jake Arrieta of the Cubs in Bill James’ Cy Young Predictor, but the narrow margin is probably due to a slight boost for Arrieta due the Northsiders outperforming the Dodgers. The raw statistics tell a tale that decidedly edges in the Los Angeles southpaw’s favor. He tops the NL in ERA, WHIP, and pitcher WAR. His WHIP of 0.64 would be the best ever, edging out all the famous pitcher seasons (1999 Pedro, 1968 Bob Gibson, any of Greg Maddux‘s four straight Cy Young seasons). But one of the more ludicrous figures is his 20.33 K/BB rate, which even if he falls off his current pace, would more than likely shatter Phil Hughes’ single season record for K/BB rate of 11.63 in 2014. As far as durability, he also leads the league in innings pitched with 100 and 2/3 over 13 starts, good for just over 7 and 2/3 innings per start.

To look beyond the surface stats we must start with a rather obvious statement: Kershaw is a strikeout pitcher. I wanted to begin to investigate his dominance by taking a look at plate-discipline data, courtesy of Fan Graphs. As one might expect, Kershaw exceeds the 2016 MLB averages (limited to starting pitchers only) in areas you’d want him to: higher O-swing rates and Zone percentage. He also stays low in areas that would indicate a lack of success for pitchers such as contact % and contact rate specifically on pitches within the strike zone.

The most notable and important disparity between Kershaw and the league average lies in that Pacific Ocean sized gulf in O-Contact%. Batters facing Kershaw only make contact on balls that end up outside of the strike-zone 42.3% of the time, versus 64.4% for the league. Were it another pitcher, one could say that perhaps the low O-contact rate stems from batters taking pitches, being patient and drawing walks, but with Kershaw’s strikeout rates and absurdly low walking rates (seriously, 6BB the entire year, compared to 122K’s!) the crooked numbers are likely do to his incredible ability to induce swings and misses outside of the zone. Comparisons between the lefty’s First Strike % (68.9%) and overall swinging strike rate (16.1%) to those of the MLB as whole this season (60.4% and 9.4%, respectively) lend further support that Kershaw is mastering the art of getting batters to not only chase more pitches out of the zone, but whiff on said pitches as well.

Kershaw has gradually (and sometimes drastically) throughout his career bettered league average O-contact and O-swing % and this continues form the backbone of his success in looking at what happens in the now rare event that a batter does make contact with a Kershaw offering outside the zone. Generally speaking, a good pitcher strives to keep his groundball rate high and his flyball rate low and Kershaw again has shown his elite ability to improve over his career in both regards. Neil Weinberg in a nifty piece further clarifies that even when flyballs are hit against the ace, there’s an ever-increasing chance that they will be more of the harmless “infield fly” variety. Here again, I want to use these sets of data with the above mentioned plate discipline statistics to drive home a logical (if not obvious) point. If Kershaw induces batters to swing out of the strike zone at an above-average cut and those swings actually make contact (remember his O-contact % is roughly 20 percentage points below the league average), the result will more often then not be a less challenging ball – a weak grounder or pop-out.

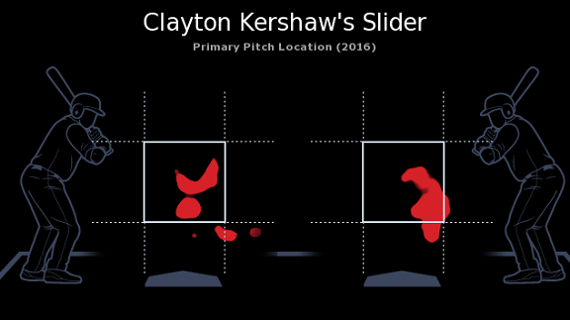

For the final insight to Clayton Kershaw’s dominance, I derived inspiration from an informative article from ESPN Stats and Information on his beastly secondary pitch: the slider. (Warning: things are about to get GIF-y). With the well-known absurdity that is the Kershaw curve (one more for good luck) and his A+ fastball, and occasionally something special, he hardly needs a dominant slider at all. As the heat map below shows, Kershaw has been burying his slider all season.

A deeper look past the interesting facts from that ESPN article intrigued me. Kershaw throws his slider at a rate of 32.7% (thus far the highest season average of his career) yielding a 39.2% strikeout rate. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find league wide K-rates by pitch but for a bit of context starters league wide threw sliders just 12.9% of the time, and the overall K-rate for the league is 20.3%. It’s hard to properly frame this discussion because we’re comparing Kershaw’s slider to all pitches thrown by starters in 2016, but the fact that a Kershaw slider is twice as likely to be a strikeout pitch than the average pitch thrown astounds me. And oh yeah, his slider is actually second to that famous curve which sits at 51.9%.

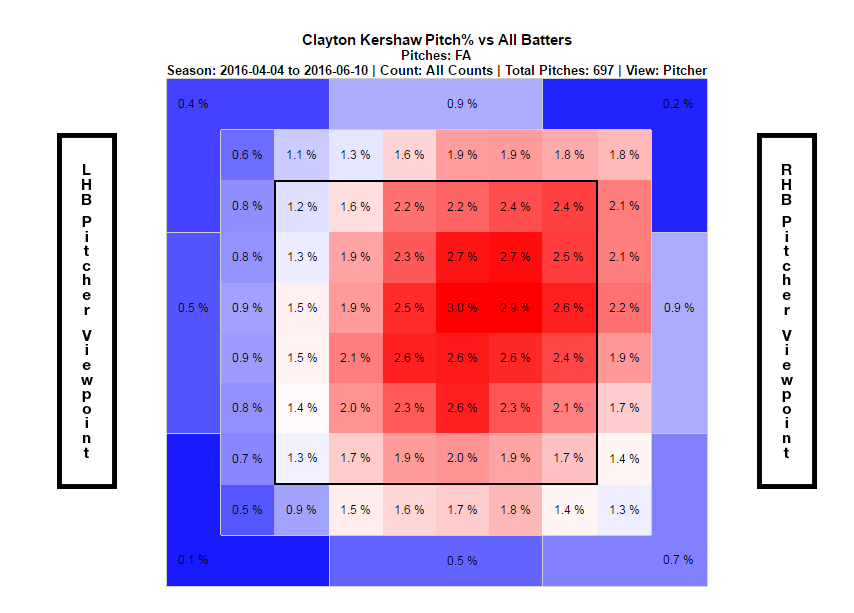

To wrap up, I’d also like to expand on the heat map included in the ESPN article. An appropriate investigation as to the effectiveness of his slider starts with looking at a representation of his primary pitch: the fastball. Take this heat map (below) and compare it to the one provided of his slider and we notice right away that Kershaw likes to pitch on the inner-third to righties, or outer-third for left-handed batters.

By dominating these areas and throwing aggressive fastballs closer to the middle of the plate, Kershaw completely bamboozles batters when he does throw the slider, as evidenced here (poor Bartolo). Because he can throw 95, Kershaw can show a number of pitches with relatively low movement in the central areas of the strike zone and then all of a sudden unleash a slider that either catches the edges of the zone, or drops out completely. Hitters have no shot as the slider looks like the fastball, but hardly acts like one.

One second the ball is there and the hitter can track it, the next it’s not. Simply call it the late, great Muhammed Ali principle: “His hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see”. And if Kershaw continues to pool all of these factors together, keep up his absurd plate discipline numbers, then he’ll surely be in line for his 4th Cy Young, and there would be much cause for dancing indeed.

-Jesse Hartman